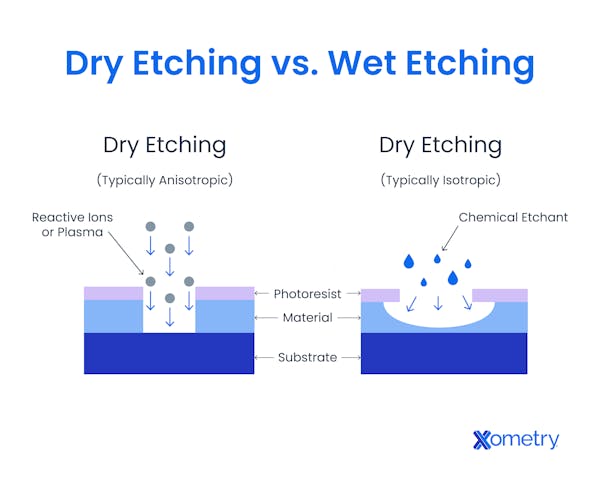

The choice between dry and wet etching is an early decision in semiconductor and microfabrication processes when defining patterning and material-removal steps. Many considerations must be taken into account to decide which etching method to use on a wafer when creating electronic components, whether it employs liquid etchants (wet etching) or gaseous species in plasma form (dry etching).

This article explains the dry and wet etching processes, their methods, and key applications. We will also clarify the differences between them and the main factors to consider when choosing between the two. If you'd like to learn more about other types of part markings, you can also visit our guide on direct part marking.

Etching Definition

Etching is a manufacturing technique used to remove layers or slices of a workpiece, including semiconductors, dielectrics, polymers, and metals. It can employ chemical corrosion, electrochemical reactions, or physical processes such as ion bombardment.

Different etching processes are used depending on the desired manufacturing outcome. The procedure for different applications can vary greatly in terms of etching chemicals, the temperature used in the process, and exposure time.

Safety is also a concern because fumes and vapors from wet etching chemicals can cause corrosion and health hazards if not properly contained or ventilated. It’s also important to take proper precautions when handling cleaning solvents used after liquid immersion or vapor-phase processing.

Etching Considerations and Performance Parameters

Before comparing wet and dry etching, it helps to understand how etching performance is evaluated.

Applying a liquid or vapor etchant causes complex molecular interactions that significantly affect the material’s surface. Regardless of the type of etching we are talking about, an etching treatment can cause one of three outcomes:

- Isotropic etching: The material is removed uniformly in all directions, creating a rounded profile or undercut beneath the mask. Since it’s a less precise form of etching, isotropic processes are used mainly for material removal and surface smoothing, not for cleaning, which is typically done using chemical cleans rather than etching.

- Completely anisotropic etching: The material is removed primarily in the vertical direction, producing sidewalls that are nearly vertical when viewed in cross-section.

- Anisotropic etching: The created shape has a form between the two mentioned above. Anisotropic etching is commonly used to create circuit patterns.

Manufacturers evaluate several key performance parameters to determine the best etching method, whether wet or dry:

- Etching rate: the speed at which etching occurs, or the thickness being etched per unit of time. It is usually measured in μm/min or nm/min (micrometers or nanometers per minute).

- Selectivity: the ratio of the etch rate of the target material to that of the mask or another material (R_target / R_mask). It is crucial for determining how well the mask can withstand the process when defining or choosing the mask.

- Etch uniformity: the etch rate variation throughout one part, multiple parts, or multiple batches of parts. It is commonly expressed as (R_max − R_min) / (R_max + R_min), describing how uniformly the material is removed across a wafer or batch.

- Anisotropy: defined as the etching directionality, meaning that when A=0, the etching is considered isotropic, and when A=1, the process is completely anisotropic.

The Wet Etching Process

Wet etching is a technique that uses a liquid solution (usually called an etchant in the liquid phase) to remove layers or portions of a workpiece, such as a silicon wafer. This process is widely used in semiconductor fabrication for wafer manufacturing and treatment. The main advantage of using it is the ability to conduct surface removal on a part-wide scale. Wet etching is often used to remove specific layers or defects on the wafer surface, rather than intrinsic impurities, which are typically controlled through doping or material growth processes.

Etchants corrode the material, and this corrosion is controlled by masks. Masks are materials that resist the etchant, protecting specific regions of the wafer to define the pattern or feature geometry.

However, the etch depth is controlled by the etch duration and rate, while the channel width can be roughly estimated as the mask opening plus twice the etch depth. Common mask materials include photoresist, silicon dioxide (SiO₂), silicon nitride (Si₃N₄), and occasionally metals such as chromium or gold, depending on the substrate and etchant used.

In wet etching, engineers typically use acids such as hydrofluoric, nitric, phosphoric, and hydrochloric. The advantages of these etchants lie in their chemical selectivity and ability to achieve uniform removal rates for specific materials.

Types of Wet Etching

Wet etching can be performed using several configurations, most commonly immersion (dip), spray, or spin etching:

- In the dip or immersion method, wafers are submerged in a tank containing the etchant solution. This traditional approach is widely used for batch processing and allows multiple wafers to be etched simultaneously.

- In spray or spin etching, the wafer is rotated while the etchant is sprayed onto its surface to enhance uniformity and reduce chemical usage. The setup typically includes a collection system for spent chemicals, not an absorption mechanism. The rotation primarily improves uniformity and distribution of the etchant, while the etch rate itself depends on the crystal orientation of the substrate, particularly in anisotropic etchants like KOH or TMAH.

Immersion etching remains the most common method for silicon wafers, while spray or spin systems are preferred when improved chemical control or reduced consumption is needed. The choice depends on material and safety considerations, not simply on acidity. Silicon wet etching in semiconductor fabrication can use either immersion or spray methods, though immersion in aqueous alkaline solutions such as KOH or TMAH is most common. It’s a misconception that wet etching always relies on immersion baths; spray and single-wafer systems are also used, particularly for modern cleanroom tools where chemical consumption and uniformity are tightly controlled.

The Dry Etching Process

Dry etching encompasses several techniques, many of which use plasma. While the term ‘plasma etching’ is sometimes used broadly, it refers more specifically to processes where chemical reactions dominate rather than purely physical sputtering. Dry etching removes material from the surface using energetic ions or reactive species generated in plasma or ion beams. Those beams contain high-energy particles (in the form of ionized gases in the plasma phase) that dislodge surface atoms, which are then removed as volatile reaction products or by physical sputtering. The etched area is then controlled via masked patterns. The process allows for high aspect ratio geometry creation.

This technique is also widely used in semiconductor fabrication. Dry etching is preferred for its reduced undercutting and its ability to produce anisotropic, high-aspect-ratio features. Etch uniformity depends on process parameters such as gas composition, pressure, plasma density, and electrode geometry. The etched profile is strongly influenced by the specific technique used.

Typical gases used in this process include oxygen, fluorocarbons, and chlorine and bromine species (in the plasma phase). Hydrogen plasmas have been investigated for surface cleaning, damage removal, and certain compound semiconductor etches, but their use remains specialized. Oxygen plasma is primarily used to etch or clean organic materials and polymers. It is generally ineffective on metals unless combined with other chemistries or used for oxide formation rather than etching.

Types of Dry Etching

Different plasma manipulation techniques and equipment give rise to several types of dry etching:

- Ion beam etching (IBE): the most straightforward of the dry etching processes. It directs argon ions onto the surface as an ion beam at energies of 1-3 keV (kiloelectronvolts). These energies are sufficient to sputter material from the surface, hence the use of ion sources to generate the beam.

- Reactive ion etching (RIE): a type of dry etching that makes use of chemically reactive species (reactive ions) that are accelerated toward a substrate (in most cases a silicon wafer). Inside the etching chamber, the wafer is placed on an RF-powered electrode that biases the ions and controls their directionality toward the surface. This allows highly anisotropic channels to form. By increasing pressure in the etching chamber, the mean free path of particles can be reduced, which translates into a less directional etching, resulting in a more isotropic channel.

- ICP-RIE etching (or simply ICP etching): uses an inductively coupled plasma source. The plasma is generated with an RF-powered electromagnetic field and added to a conventional RIE system, allowing greater control over plasma density and ion energy.

- Plasma etching: a subclass of dry etching capable of creating isotropic etch profiles. It is often used to remove whole film layers. In plasma etching, the substrate is exposed mainly to neutral radicals and low-energy ions that chemically react with the surface, so the process is generally more isotropic than RIE. Many dry etching processes are plasma-based, so the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, although not all dry etching relies on plasma chemistry.

Considering the techniques described above, dry etching methods can be further categorized as follows:

- Chemical reaction processes: those that use plasma or reactive gases (plasma etching).

- Physical removal processes: that make use of momentum transfer to knock off material (IBE).

- A combination of the two above (RIE and ICP etching).

Reactive gases used in dry etching, such as fluorocarbons and chlorine compounds, pose chemical and toxicity hazards. However, these processes are conducted in sealed vacuum systems with exhaust scrubbing, which minimizes operator exposure. While more complex than wet etching, dry etching allows precise patterning and surface modification of wafers through controlled chemical and physical reactions.

Dry Etching vs. Wet Etching

After understanding both processes, the key differences and applications between dry and wet etching can be compared.

Generally speaking, wet etching uses simpler equipment, is less complex, and typically achieves higher etch rates than dry etching. It's also more highly selective. However, wet etching also requires larger chemical volumes and poses greater handling and contamination risks compared to dry etching, and it offers less control over feature geometry. Dry etching, on the other hand, offers strong anisotropic control, higher precision, and generally safer operation within sealed vacuum systems. Depending on the process, dry etching can achieve moderate to high etch rates while consuming less reagent volume than wet processes. However, it is a more complex process, requiring more sophisticated equipment, and it offers lower selectivity.

Both techniques are widely used in:

- Semiconductor fabrication

- Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) production

- PCB fabrication (primarily wet etching)

- Thin-film and metal micro-etching

- Transistor gate patterning (primarily dry etching)

Both techniques use etchants, either in gas or liquid form, to remove material from part surfaces. Silicon processing is the most common use case. With anisotropy being critical in micro- and nano-scale semiconductor structures, dry etching offers many advantages over wet etching for precision pattern transfer.

The choice between dry and wet etching often comes down to control versus simplicity. Wet etching remains unmatched for throughput and ease, but when geometry precision or feature definition really matters, dry etching is the engineer’s most reliable tool.

Etching with Xometry

Both dry and wet etching play crucial roles in modern manufacturing, especially in microelectronics and semiconductor fabrication.

Dry and wet etching are essential in electronics manufacturing, each suited to different project requirements. The main difference between them lies in the state and mechanism of the etchant: liquid-phase chemistry for wet etching versus plasma or ion-based reactions for dry etching.

Interested in how Xometry can help with your manufacturing needs? Xometry provides a wide range of manufacturing capabilities, including 3D printing and other value-added services for all of your prototyping and production needs. Visit our website to learn more or to request a free, no-obligation quote.

Disclaimer

The content appearing on this webpage is for informational purposes only. Xometry makes no representation or warranty of any kind, be it expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or validity of the information. Any performance parameters, geometric tolerances, specific design features, quality and types of materials, or processes should not be inferred to represent what will be delivered by third-party suppliers or manufacturers through Xometry’s network. Buyers seeking quotes for parts are responsible for defining the specific requirements for those parts. Please refer to our terms and conditions for more information.