Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel: What Is It, How It Works, Process, and Advantages

Learn everything there is to know about precipitation hardening, what it is, and how it is used to make alloys even more durable and efficient.

Precipitation hardening of stainless steel is a process that is used for making an excellent class of alloys that have the advantages of both martensitic and austenitic grades of steel. The specialized heat treatment process that they go through gives the alloys increased tensile strength (from 850 MPa to 1,700 MPa) while keeping their effectiveness and ductility.

The precipitation hardening (PH) process has been adopted by many Xometry users in all different industries, from oil & gas to aerospace. There are several steps involved in precipitation hardening, including dissolving, rapid cooling, and aging, and we’ll look at each of these below in detail. We’ll also cover just what precipitation-hardened stainless steel is, how it works, and its advantages and disadvantages.

What is Precipitation Hardening of Stainless Steel?

Precipitation hardening of stainless steels creates a family of alloys made up of iron, chromium, and nickel. PH steel is created when we add aluminum, copper, molybdenum, titanium, or niobium and then heat treat it. One or more of these materials can be added, and the final result offers the perfect blend of martensitic and austenitic grade characteristics.

The process gives the material all the good martensitic and austenitic benefits, namely enhanced strength and corrosion resistance respectively. PH stainless steels have tensile strengths ranging from 850 MPa to 1,700 MPa, and yield strengths from 520 MPa to over 1,500 MPa.

The treated steel can have elongation levels from 1 to 25%, and cold working the steel before aging can make it even stronger. PH stainless steel alloys are available in annealed (Condition A) and tempered (Condition C) states. Annealed state alloys are relatively soft and malleable, with Rockwell hardness ranging from B75 to C20. For a higher Rockwell hardness of C35 to C49, the parts can then go through the age-hardening process.

The main purpose of PH stainless steel is to create a material with the strengths of both austenitic and martensitic stainless steels, namely exceptional strength and corrosion resistance. PH is often used in aerospace, marine, medical, and automotive industries as the controlled heat treatment allows engineers to bespoke the material's properties according to their exact needs.

Precipitation-hardened stainless steel is commonly used in aerospace, automotive, oil and gas, and many other industrial applications.Jake ThompsonSenior Solutions Engineer

What Is the History of Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel?

The process of precipitation hardening stainless steel dates back to the early 20th century. In 1929, an inventor from Luxembourg, William J. Kroll discovered that adding titanium to stainless steel, then heat treating it, made the steel much stronger. After that, he created the Kroll process—the method of making metallic titanium from titanium tetrachloride. In the 1940s, precipitation hardening metals gained momentum, and the first martensitic PH stainless steel was designed.

In 1948, the American Rolling Mill Company’s work led to the birth of 17-4 PH steel which has been widely used since in aircraft landing frames, fasteners, and engine components, and is a popular choice among Xometry customers. 15-5 PH stainless steel entered the scene when chromium use was reduced and replaced by nickel within the 17-4 PH group. The advancements in technology and science in recent years has led to a mass rise in PH stainless steel. One of these newer PH steels, Ferrium S53, is used in aerospace thanks to its corrosion resistance and high strength, and is an example of just how far PH has come.

How Does Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel Work?

Precipitation hardening stainless steel works through a controlled heat treatment process that gives PH stainless steel improved strength by forming fine precipitates within its microstructure. The process starts by heating the alloy with a solution treatment which then turns into a solid solution. This step is followed by rapid cooling (or quenching) which traps the alloying elements in the crystal structure. The last step is aging. This is where the metal is reheated and turned into fine particles. This phase stops any potential dislocation or movement, and increases the material’s strength. For extra strength and hardness, some choose to cold work the material during the aging process.

What Is the Purpose of Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel?

The primary purpose of PH stainless steel is to offer a material that combines the strengths of austenitic and martensitic stainless steels. It aims to provide exceptional strength, tailored properties, and corrosion resistance for demanding applications. Through a controlled heat treatment process, PH stainless steel achieves improved strength by forming fine precipitates within its microstructure. This process allows engineers to customize the material's properties to meet specific needs, striking a balance between strength, ductility, toughness, and corrosion resistance. It finds utility in diverse industries like: aerospace, marine, medical, and automotive, offering enhanced performance and durability.

What Are the Phases of the Precipitation-Hardening Stainless Steel Process?

The PH process involves three main phases—solutionizing (heating to dissolve alloying elements), quenching (rapid cooling to trap these elements in solution), and aging (controlled reheating to allow the precipitates to form)—where the metal goes through a series of metallurgical changes during heat treatment.

Here's a general overview of how the PH process works.

1. Solutionizing

The first PH step is known as solutionizing. Also known as the "solution treatment," this step involves dissolving precipitates and minimizing the potential for the alloy to separate. The material is heated to its solvus temperature and kept there until a uniform solid solution is made. It is then taken away from the heat source.

2. Quenching

The next stage involves the rapid cooling or “quenching” of the alloy. By cooling the material so quickly, a supersaturated solid solution with lots of extra copper components is created. The quickness also prevents nucleation sites and precipitates from forming on the alloy.

3. Aging

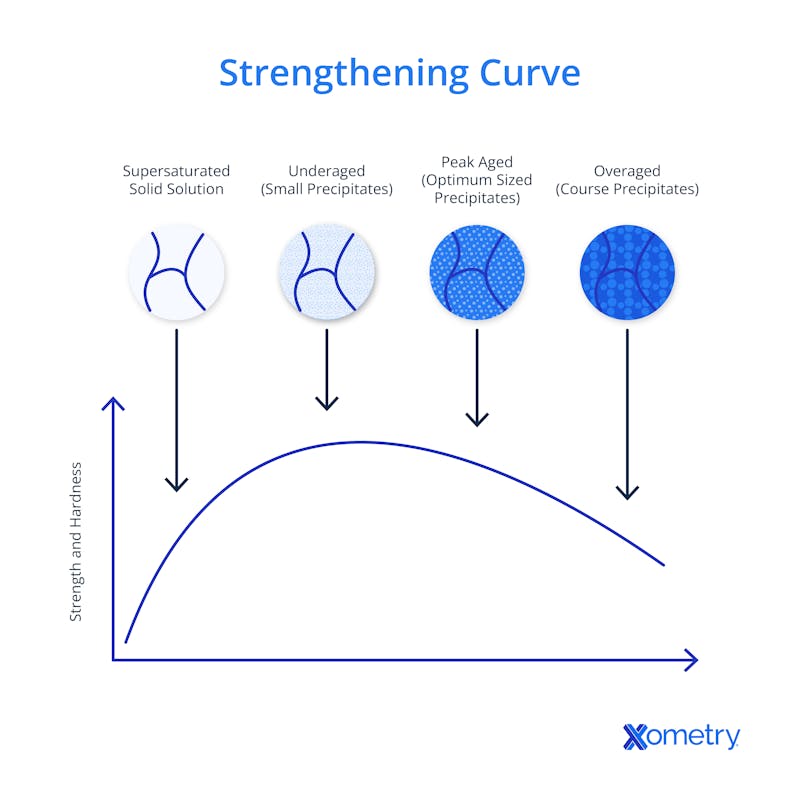

The final stage in the PH process is aging. This is where the material goes through more heat treating, but this time below the solvus temperature. This allows the atoms to diffuse slightly over short distances, resulting in the creation of finely dispersed precipitate layers within the material. It makes the alloy stronger by limiting dislocation movement. To achieve maximum strength it is crucial that the material is aged for the optimal amount of time, otherwise precipitates may be too small (underaged) or too large (overaged) to effectively prevent dislocation movement. The aging-to-strength curve is outlined in the graphic below:

What Are the Requirements of Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel?

PH stainless steels have specific requirements to make them suitable for different uses. First, their alloy composition includes elements like iron, chromium, nickel, and additional additives such as copper, aluminum, and titanium. These materials are important in the PH process as they give the final material its amount of strength and corrosion resistance.

Another important requirement for creating the proper microstructure for a strong, durable, and resistant steel is sticking to the above process phases (solution treatment, quenching, and aging). Ultimately, you want the best balance between strength and impact resistance. Weldability is another requirement to prevent cracking, and loss of mechanical properties, and corrosion resistance during welding.

How Long Does Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel Take?

Precipitation hardening can be a sluggish process lasting anywhere from one to 24 hours. The dissolving stage can last up to four hours. The quickest phase is quenching which usually takes just a few minutes. The length of the aging step can vary, but it can last up to a day. If you go for the natural aging method, this can last a few weeks. Depending on the result you’re after, there are different times for each step, so precise calculations of both time and temperature are important.

For your ease of reference, we’ve put the optimal hardening temperatures and duration for some alloys in the table below.

| Type | Hardening Temperature | Hardening Time |

|---|---|---|

Type H900 | Hardening Temperature 482 °C | Hardening Time 1 hour |

Type H925 | Hardening Temperature 496 °C | Hardening Time 4 hours |

Type H1025 | Hardening Temperature 552 °C | Hardening Time 4 hours |

Type H1075 | Hardening Temperature 580 °C | Hardening Time 4 hours |

Type H1100 | Hardening Temperature 593 °C | Hardening Time 4 hours |

Type H1150 | Hardening Temperature 621 °C | Hardening Time 4 hours |

Table Credit: https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=2819

At What Temperature Does Precipitation Hardening of Stainless Steel Occur?

The temperature that PH of stainless steel occurs depends on the different stainless steel types and your desired outcome. Martensitic PH steels, for example 17-4 PH, goes through the martensite transformation at the relatively low temperature of around 250 °C. Kicking it up a few notches to anywhere between 480 °C and 620 °C will make the material even stronger.

Austenitic-martensitic PH steels are already fully austenitic after just the solution treatment. To start the martensite process, another heat treatment at 750 °C for two hours, followed by cooling to room temperature, is necessary. Some alloys need to be refrigerated at temperatures as low as -50 °C to -60 °C for eight hours to get that stable austenitic/martensitic structure.

What Are the Different Types of Precipitation-Hardening Stainless Steel?

The different types of PH stainless steel are characterized into four groups, based on their final microstructures after the heat treatment. These are:

1. Semi-Austenitic PH Stainless Steels

Once cooled from the annealing temperature to room temperature, the semi-austenitic PH steels will keep its austenitic make-up which is tough and ductile, and better suited for cold-forming processes than martensitic PH steels that tend to be rather on the hard side. To harden and strengthen this type of steel, it must first be converted from austenite to martensite which will then prep the material for the aging process. To reduce the presence of austenite-stabilizing elements, semi-austenitic PH steels need to be heated to 650–870 °C.

This partially transforms the material to martensite upon it’s cooled to room temperature, but it can also be achieved by refrigeration below the beginning of martensite transformation (Ms temperature) or through cold working. The reinforcement of semi-austenitic PH stainless steels has a two-step approach. After the initial martensite treatment, the second phase involves exposure to the aging temperature of 455–593 °C, which leads to precipitation, resulting in hardness and overall strengthening.

2. Austenitic PH Stainless Steels

Austenitic alloys keep their structures through annealing and aging. At the annealing temperature of 1,095–1,120 °C, the precipitation hardening phase dissolves and stays in the solution during rapid cooling. Precipitation happens when the alloys are reheated at 650 to 760 °C. This results in increased hardness and strength (although it won’t be as hard as its martensitic or semi-austenitic counterparts) and they’ll also keep their non-magnetic properties.

3. Welding PH Stainless Steels

Welding will bring out areas of solution-treated or annealed base metal. For optimal harness in these zones, you may have to do some double or single post-weld heat treatments. The steel manufacturer will be your best point of call for welding and treatment guidance on the particular steel that you’re working with, but if you have any good books on the subject, you can always refer to them. Thinner PH stainless steel sections generally don’t need any preheating before welding. The martensitic PH grades, which have low-carbon content, don’t go through a full hardening like, for instance, the type 410.

With single-pass welds, both the weld metal and the heat-affected zones tend to respond together to post-weld precipitation hardening treatments. Multiple-pass welds aren’t as uniform and this tends to cause differences in the base and weld metals, and the heat-affected zones. Annealing after welding will ensure a more consistent and uniform outcome.

For example, when welding a 17-4 PH plate that’s under four inches thick, you might find that the instructions will recommend interpass temperatures up to 150 °C, but preheating isn't mandatory. When it comes to 17-4 PH with plate thicknesses of over four inches, preheating at 95 °C and keeping an interpass temperature of 95–260 °C will likely be necessary. When welding 17-4 PH using bare ER630 wire, you can use argon for GMAW welding, or helium/argon gas for GTAW welding.

4. Martensitic PH Stainless Steels

At annealing temperatures ranging from approximately 1,040 to 1,065 °C, martensitic alloys, in particular, will have mainly austenitic structures. When cooled to room temperature, these alloys go through a transformative process that turns the austenite structure into martensite. Quickly cooling the material in air or oil after that will keep the additives, like copper and columbium, within the solid solution at room temperature. The austenite to martensite transformation happens at roughly 150 °C to room temperature. After that, reheating this supersaturated solid solution in the martensite matrix at the aging temperature of 482 °C to 593 °C will produce minute particles precipitate for an even harder and stronger result.

Need Custom PH Stainless Steel Parts?

What Are the Uses of Precipitation-Hardened Stainless Steel?

Precipitation-hardened steel is used in many industries and sectors. In the oil & gas industry, the PH of steel is used for gates, valves, machinery components, retaining rings, springs, and spring holders. In automotive, it’s used for engine parts, gears, shafts, balls, plungers, bushings, chains, valves, and gears. PH steel is also used on aircraft components, airplane engine parts, and turbine blades. Other uses include valve stems, molding dies, processing equipment, fasteners, nuclear waste containers including pressure vessels, and seals in general industrial use.

Is Precipitation-Hardened Stainless Steel Used in the Aerospace Industry?

Yes, precipitation-hardened stainless steel is commonly used in the aerospace industry. Aerospace components subjected to high stress, extreme temperatures, and harsh environments benefit from the enhanced strength and corrosion resistance offered by precipitation-hardened stainless steel. Aircraft parts such as turbine blades, engine components, landing gear, fasteners, structural elements, and other critical components often incorporate precipitation-hardened stainless steel grades to ensure optimal performance and safety.

What Metals Can Be Precipitation Hardened Beside Stainless Steel?

A variety of metals beyond stainless steel can undergo precipitation hardening, enhancing their mechanical properties for specific applications. Some notable examples include:

1. Magnesium

Precipitation hardening is employed in certain magnesium alloys to improve their strength and performance, particularly in industries such as aerospace and automotive.

2. Titanium

Titanium alloys can also be subjected to precipitation-hardening processes to enhance their mechanical properties, making them suitable for aerospace, medical, and other demanding applications.

3. Steels

Apart from stainless steel, other steel alloys can undergo precipitation hardening. This technique can be employed to tailor the mechanical properties of specific steel grades, such as high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels.

4. Aluminum Alloys

Similar to stainless steel, various aluminum alloys can be precipitation hardened to improve their strength and durability. This is especially common in aerospace and structural applications.

5. Nickel

Certain nickel-based alloys, often used in high-temperature and corrosive environments, can undergo precipitation hardening to enhance their resistance to both mechanical and environmental stressors.

How Much Does a Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel Cost?

The cost of precipitation hardening stainless steel can vary widely depending on factors such as: the specific alloy composition, the quantity being purchased, market demand, supplier pricing, and regional factors. Generally, precipitation-hardened stainless steel tends to be more expensive than standard austenitic stainless steel due to its specialized properties and manufacturing processes.

The addition of alloying elements like: copper, molybdenum, aluminum, and titanium, as well as the specific heat treatment processes involved in precipitation hardening, contribute to the higher cost of these materials. Precipitation-hardened stainless steel typically falls within the range of $700–$1,000/ton. For accurate and up-to-date pricing, it's recommended to contact stainless steel suppliers, distributors, or manufacturers and request quotes based on your specific requirements and quantities.

Does Precipitation Hardening Costs Vary on What Metal Is Used?

Yes, the cost of precipitation hardening can vary based on the specific alloy or metal used. Different metals have varying raw material costs, availability of alloying elements, and manufacturing processes, all of which contribute to differences in pricing.

What Are the Advantages of Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel?

There are many advantages to PH stainless steel, and these far outweigh the disadvantages. Thanks to the development of a sturdier microstructure within the metal, PH can make metal up to four times stronger. The process can also improve the material’s ductility which will help against cracking and breakage. It makes the metal more corrosion resistant, and gives it a sort of shield against wear and tear.

Precipitation-hardening reinforces stainless steel's high strength, hardness, and corrosion resistance capabilities. However, it is sensitive to cracking under intense heat, therefore, welding PH SS is a difficult process.Jake ThompsonSenior Solutions Engineer

What Are the Disadvantages of Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel?

Despite its advantages, PH does come with a few cons that need consideration. Using too high a heat during the PH process can make the metal brittle, or cause it to crack or warp during the quenching phase. It’s also a time-consuming and intricate process that needs very specialized equipment which is sometimes hard to get. It also requires expertise, and precise time and temperature calculations (which is why it’s typically reserved for high-end applications where increased strength justifies the higher investment). Its high cost, lengthy process, and demand for precision means that it’s not always feasible for some applications and can lead to higher material costs.

Frequently Asked Questions About Precipitation-Hardening Stainless Steel

Can Precipitation Hardening Be Reversed?

Yes, the effects of precipitation hardening can be reversed through a process known as "overaging" or "overage annealing." Precipitation hardening involves the controlled formation of fine precipitates within a material's microstructure to increase its strength and hardness. However, these precipitates can continue to grow and coarsen over time. This can lead to a reduction in mechanical properties such as strength and hardness, and an increase in ductility.

By subjecting the material to elevated temperatures for an extended period, the coarsening of the precipitates can be encouraged, effectively reversing the strengthening process. This process is often referred to as "overaging" because it involves aging the material beyond the point at which its mechanical properties are optimized.

It's important to note that the specifics of overaging, including temperature and duration, will depend on the material's composition and the desired outcome. Overaging can be a deliberate step in certain applications for which a balance between strength, toughness, and other properties is desired.

Also, in some cases, the production methods could initiate the early onset of the final age-hardening phase. This can be counteracted, however, by subjecting the material to re-solution treatment before proceeding with subsequent manufacturing steps.

Is Precipitation Hardening the Same as Hardening?

No. Precipitation hardening and hardening are related but are distinct processes in materials science. Hardening is a general term used to describe the process of making a material, typically a metal or an alloy, harder by altering its microstructure through various methods. This often involves heating the material to a specific temperature and then rapidly cooling it, which can result in changes to its crystal structure and mechanical properties. Hardening can also involve introducing certain alloying elements to the material. Hardening can be achieved through processes like quenching and tempering in steel, during which the material is heated and then cooled rapidly (quenched) to lock in a hardened state, followed by controlled reheating (tempering) to achieve a balance between hardness and toughness.

Precipitation hardening, on the other hand, is a specific type of hardening process that involves the formation of finely dispersed precipitates within the material's microstructure. These precipitates, often on the nanoscale, contribute to increased strength and hardness. The process typically includes steps such as solution treatment (heating to dissolve alloying elements), quenching (rapid cooling to trap these elements in solution), and aging (controlled reheating to allow the precipitates to form). This process is commonly used in certain stainless steels, aluminum alloys, and other materials to achieve tailored mechanical properties.

Is 18-8 (Type 304) Stainless Steel Hardened?

No. Type 304 (18-8) is categorized as an austenitic steel characterized by at least 18% chromium and 8% nickel content, along with a maximum carbon content of 0.08%. This non-magnetic steel doesn't gain hardness through heat treatment; instead, achieving elevated tensile strengths requires cold working.

If you are interested in utilizing PH stainless steel for your next project, be sure to use the Xometry Instant Quoting Engine® to get an instant quote on a variety of materials, including 17-4 PH and 15-5 PH stainless steels.

Copyright and Trademark Notices

- Ferrium® S53�® is a registered trademark of QuesTek Innovations LLC.

Disclaimer

The content appearing on this webpage is for informational purposes only. Xometry makes no representation or warranty of any kind, be it expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or validity of the information. Any performance parameters, geometric tolerances, specific design features, quality and types of materials, or processes should not be inferred to represent what will be delivered by third-party suppliers or manufacturers through Xometry’s network. Buyers seeking quotes for parts are responsible for defining the specific requirements for those parts. Please refer to our terms and conditions for more information.