Injection molding is a manufacturing process used to create identical plastic parts by injecting molten plastic into precision molds. Injection molding starts with feeding thermoplastic pellets into a heated barrel, where they are melted and then forced into a mold cavity under high pressure. The mold opens, and the part is ejected once the material cools. Common types of injection molding include standard, gas-assisted, liquid silicone rubber (LSR), thin-wall, and micro molding, though other variants such as overmolding and insert molding are also widely used. Standard molding is ideal for producing large, durable parts, while gas-assisted molding reduces material use and improves surface quality. Liquid silicone molding is used for producing flexible, heat-resistant parts, and thin-wall molding is commonly employed for lightweight packaging. Micro molding is used for creating small, precise components for electronics and medical devices.

Injection molding machines consist of three key components: the injection unit, which melts and injects the plastic; the clamping unit, which secures the mold during injection and cooling; and the mold system, which shapes the part. Hydraulic, electric, and hybrid machines use precise controls to ensure consistent quality throughout the molding process.

The global injection molding market was valued at roughly $150–180 billion as of 2024, driven by demand in industries like packaging, automotive, electronics, and healthcare. Manufacturers produce a wide range of products, from caps and dashboards to phone cases, syringes, and housings. Automotive components are often lightweight, while medical devices, consumer goods, packaging, and household products are other common applications. Injection molding offers key advantages such as high-volume efficiency, flexible design options, and a wide range of material choices, making it an ideal method for producing consistent parts with minimal waste. Its main drawback is the high cost of tooling, which can limit low-volume production and complicate rapid design modifications due to lengthy mold change times.

What Is Injection Molding Definition?

Injection Molding is a manufacturing process that injects molten plastic into a mold to form parts. The process begins by feeding plastic pellets into an injection barrel where they are heated until molten. The liquid mixture funnels into molds, where pressure shapes it into tight forms before cooling. The process permits the creation of complex, high-volume, and durable parts with minimal waste. Initial applications included small items (combs and buttons), but it has since become a popular choice for a wide range of products. James Watson Hendry pioneered screw-based injection molding and later developed gas-assisted injection molding, which enabled complex, hollow parts with improved design flexibility, strength, and surface finish.

Injection molding is explored in a variety of studies and research. One study confirmed that higher mold temperature and injection pressure affect the polymer's mechanical properties, causing product distortion, according to a study titled "Advanced Injection Molding Methods: Review" by Mateusz Czepiel and Agnieszka Sobczak-Kupiec, dated August 24, 2023.

Basic information on manufacturing processes (injection molding) covers machine components and materials used. It notes that injection molding power varies with factors (material's specific gravity, melting point, thermal conductivity, and part size), according to research titled "Manufacturing Processes Reference Guide" by Robert H. Todd and Dell K. Allen, dated June 15, 1994.

Another research highlights the gate freeze-off time's role in injection molding, affecting cycle time and product quality. Increasing hold time and weighing the part identify gate freeze-off (part's weight stabilizes), according to the study titled "Analysis of Gate Freeze-Off Time in Injection Molding”, by Dr. R. Pantani and F. De Santi, dated March 24, 2004.

Who invented Injection Molding?

John Wesley Hyatt invented the first injection molding machine in 1872 to produce billiard balls using celluloid. Raymond Welch later developed metal injection molding in the 1970s for precision metal parts. Injection Molding began in the late 19th century, when John Wesley Hyatt and Isaiah (John’s brother) patented the first injection molding machine in 1872. The original design used a plunger to inject heated celluloid into a mold, producing items (billiard balls and combs). The invention responded to the demand for a substitute for ivory, which had become scarce and expensive. Early machines operated manually and supported basic shapes with limited precision. The process gained industrial relevance by offering a faster and more scalable method for forming plastic parts.

James Watson Hendry introduced the first commercially successful screw injection machine in the 1940s, which improved control and consistency, supported complex designs, and expanded the use of thermoplastics. Raymond Welch developed metal injection molding in the 1970s for small, durable metal parts with intricate shapes. The process adapted plastic injection principles to powdered metals with sintering, finding applications in aerospace, medical devices, and firearms. Liquid silicone rubber molding was commercialized in the late 1970s and became widespread through the 1980s, using two-part silicone compounds injected into heated molds to produce flexible, heat-resistant parts (gaskets, seals, and baby bottle nipples).

The gas-assisted injection molding gained popularity in the 1990s for creating hollow parts with less material. The process injected nitrogen gas into the molten plastic to push the material outward, resulting in lightweight components with smooth surfaces. Uses included furniture, automotive panels, and appliance housings. Each innovation addressed a specific manufacturing challenge and enhanced the capabilities of injection molding. The Injection Molding history reflects a series of innovations driven by material science, industrial demand, and precision engineering. The injection molding process has evolved since John Wesley Hyatt invented it.

What Is the Process of Injection Molding?

The process of Injection Molding is shown in the table below.

| Process Name | Definition | Type |

|---|---|---|

Process Name Clamping | Definition Mold halves close and lock in place to prepare for injection. | Type Hydraulic machines apply high force. Electric machines use servo motors for precision. |

Process Name Injection | Definition Molten plastic enters the mold cavity through a nozzle under pressure. | Type Micro molding requires tight control. Gas-assisted molding uses nitrogen to shape hollow parts. |

Process Name Packing / Holding | Definition Pressure remains to compensate for material shrinkage and ensure full cavity fill. | Type Thin-wall molding demands rapid packing. Structural foam molding uses lower pressure. |

Process Name Cooling | Definition Material solidifies inside the mold as heat is removed or, in thermoset processes, as curing completes. | Type Liquid silicone rubber molding cures rapidly under heat, while standard thermoplastic molding uses water channels for temperature control. |

Process Name Mold Opening | Definition Mold halves separate after cooling completes. | Type Hybrid machines balance speed and force. Electric machines allow faster cycles. |

Process Name Ejection | Definition An ejected part exits the mold using ejector pins or plates. | Type Multi-cavity molds eject several parts. Micro molding uses precision ejectors. |

What Is the Injection Molding Machine?

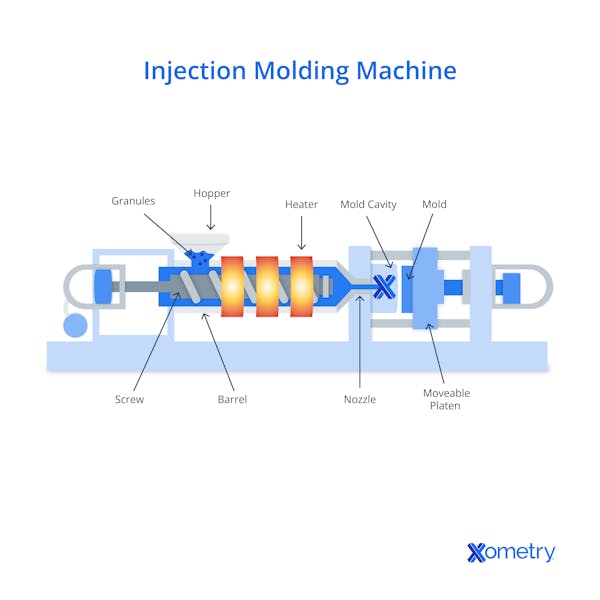

The Injection Molding Machine is used to create plastic components by heating primarily thermoplastic pellets and injecting the molten material into a mold cavity under high pressure. The machine operates by converting solid plastic pellets into precisely shaped parts through a controlled heating and molding process. It begins by feeding the raw material into a hopper, where gravity guides the pellets into a heated barrel. Heaters melt the plastic while a rotating screw moves the molten material forward inside the barrel, ensuring thorough mixing. The screw injects it through a nozzle into the mold cavity. The mold system, including the core, cavity, and cooling channels, shapes the final product and ensures dimensional stability during cooling once the plastic reaches the proper viscosity. The clamping unit holds the mold halves together during injection and cooling, applying the necessary force to maintain mold integrity. The mold opens, and the part is ejected using ejector pins once the plastic solidifies.

The main components of injection molding machines include the hopper, barrel, heaters, screw, nozzle, clamping unit, and mold system. The hopper stores and feeds the plastic pellets. The barrel contains the screw and heaters, which melt and move the material. The nozzle guides the molten plastic into the mold cavity. The clamping unit keeps the mold closed during injection and cooling. The mold system shapes the final product and influences its complexity and precision. Each part contributes to a distinct phase of the process, ensuring consistent quality and repeatability. Brands (Arburg, Engel, and Haitian) manufacture machines across various capacities and configurations. Entry-level models of the Injection Molding Machine start around $10,000, while high-performance systems can exceed $200,000, depending on size and automation level. Injection molding cost estimation tools typically calculate production costs by considering part geometry, material type, mold complexity, and production volume.

What Are the Types of Injection Molding Machines?

The types of injection molding machines include hydraulic, electric, and hybrid. Each type offers different molding technologies tailored to speed, precision, and material handling. Hydraulic injection molding machines use fluid pressure to perform injection and clamping, making them ideal for applications requiring large clamping forces, such as automotive parts, large industrial components, and thicker parts. The machines provide flexibility and are cost-effective for high-volume production. Electric injection molding machines utilize servo motors for precise control of each movement, making them suitable for cleanroom environments and applications such as medical devices, electronics, micro parts, and components requiring tight tolerances and high precision. Hybrid machines combine the power of hydraulic systems with the precision and energy efficiency of electric controls, making them suitable for industries like packaging, consumer goods, and multi-cavity molds.

Each machine type is aligned with specific molding technologies. Hydraulic machines are well-suited for gas-assisted molding and structural foam molding, where high injection force and mold fill control are critical. Electric machines excel in micro molding and thin-wall molding, where speed and precision are essential for high-quality parts. Hybrid machines provide flexibility for standard thermoplastic molding and, with appropriate modification, can also process liquid silicone rubber using dedicated dosing and heating systems. The choice of injection molding machine is integral to determining the right molding process, with factors such as clamping force, injection speed, machine control systems, and production volume influencing material selection, mold design, and overall operational cost. Each configuration is designed to address specific manufacturing needs, enhancing part consistency, reducing energy consumption, and improving production efficiency.

What Is the Injection Molding Diagram?

An injection molding diagram illustrates the entire process of converting plastic pellets into shaped parts using heat, pressure, and precision tooling. Each component in the process has a specific function and role. The diagram typically starts with the hopper, which stores and feeds thermoplastic pellets into the system. The barrel receives the pellets, where heaters melt the plastic in distinct zones (feed, compression, and metering), and the screw rotates to feed, melt, and mix the plastic. The nozzle then directs the molten plastic into the mold cavity under controlled pressure and flow rates. The clamping unit securely holds and aligns the mold halves under high pressure during injection, ensuring precise part formation. The mold cavity defines the part’s shape and size, with the ejector pins (sometimes assisted by a spring or ejector plate) pushing the finished part out after cooling. The diagram demonstrates how mechanical, thermal, and pressure systems work in sync to produce high-quality, precise plastic parts.

What Are the Materials for Injection Molding?

The materials for Injection Molding are listed below.

- ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene): ABS offers high impact resistance and dimensional stability. Common applications include automotive trim, consumer electronics housings, and protective gear.

- ASA (Acrylonitrile Styrene Acrylate): ASA resists UV degradation and maintains color over time. It suits outdoor products such as garden tools, exterior panels, and sporting equipment.

- Polycarbonate (PC): Polycarbonate provides excellent toughness and optical clarity. It supports safety goggles, medical devices, and transparent enclosures.

- Polypropylene (PP): Polypropylene resists fatigue and chemical exposure. It fits food containers, automotive battery cases, and living hinges.

- Polyethylene (PE): Polyethylene offers flexibility and moisture resistance. It supports packaging films, squeeze bottles, and storage bins.

- Polystyrene (PS): Polystyrene delivers rigidity and cost efficiency. It suits disposable utensils, CD cases, and lightweight enclosures.

- Nylon (Polyamide): Nylon provides high strength and wear resistance. It supports gears, bushings, and mechanical components.

- POM (Polyoxymethylene / Acetal): POM offers low friction and dimensional accuracy. It fits precision parts such as zippers, fasteners, and valve components.

- TPU (Thermoplastic Polyurethane): TPU combines elasticity with abrasion resistance. It suits footwear soles, flexible tubing, and protective cases.

- Liquid Silicone Rubber (LSR): LSR withstands heat and maintains flexibility. It is an injection molding material selection that supports baby bottle nipples, medical seals, and automotive gaskets.

“When designing parts for injection molding, precision starts long before the mold is built. The best designs anticipate flow, cooling, and ejection so that quality is engineered, not inspected.”Audrius Židonis; Principal Engineer at Zidonis EngineeringNote from the Editor

What Are Thermoplastics in Injection Molding?

Thermoplastics in Injection Molding refer to polymers that soften when heated and solidify upon cooling, allowing them to be reheated and reprocessed multiple times without altering their chemical structure. Thermoplastics are foundational materials for manufacturing due to their adaptability, cost-efficiency, and compatibility with molding processes. Thermoplastics consist of polymer chains with repeating monomers that respond predictably to temperature changes. The behavior supports streamlined production cycles and contributes to reduced energy consumption during molding. The ability to reheat and reuse thermoplastics lowers material waste and simplifies recycling procedures. Injection molding machines designed for thermoplastics operate with precise temperature control and consistent pressure, which supports uniform part formation and minimizes defects.

The use of thermoplastics influences machine configuration, including barrel design, screw geometry, and nozzle specifications. The components must accommodate the flow characteristics and melting points of selected resins. Mold design adapts to thermoplastic behavior by incorporating cooling channels, gate placement, and ejection systems that maintain dimensional accuracy and surface finish. Implementation types (multi-shot molding, overmolding, and insert molding) rely on thermoplastics to bond layers or encapsulate components without compromising structural integrity.

Thermoplastics support a wide range of applications due to their mechanical diversity, chemical resistance, and aesthetic flexibility. Material selection affects mold longevity, cycle time, and part performance, making thermoplastics integral to process planning and product development. The role of Thermoplastics in Injection Molding extends across industries, including automotive, medical, consumer electronics, and packaging, where consistent quality and scalable production remain essential.

Is polypropylene in injection molding lightweight and chemical-resistant?

Yes, polypropylene in injection molding is lightweight and chemical-resistant. Polypropylene belongs to the category of commodity thermoplastics identified as cost-effective and widely applicable in high-volume production. The material exhibits low density, which contributes to reduced part weight and supports efficient material usage across large manufacturing runs. The material’s behavior during injection molding supports applications requiring flexibility, impact resistance, and moisture tolerance, making it suitable for diverse industrial and consumer products.

What Are Thermosets in Injection Molding?

Thermosets in Injection Molding refer to polymers that undergo irreversible chemical curing when exposed to heat or catalysts. Thermosets are materials that transition from a liquid or soft solid into a rigid structure, forming cross-linked molecular bonds that resist melting or reshaping after curing. The use of thermosets alters production efficiency by eliminating the feasibility of remelting and reshaping, which reduces rework but increases the importance of precision during initial molding. Machines configured for thermoset molding require specialized temperature control systems and metering equipment to manage the curing process. These machines differ from thermoplastic ones by using cooled barrels and heated molds to prevent premature curing. Machine parts (barrels, screws, and nozzles) need to handle lower viscosity fluids and manage reaction timing carefully to avoid forming solids too early.

Implementation types involving thermosets include compression molding and reaction injection molding, where material behavior supports large part formation and uniform pressure distribution. Mold designs for thermosets differ from thermoplastic molds by incorporating features that manage heat transfer and curing uniformity. Cooling channels, venting systems, and mold surface treatments contribute to dimensional stability and surface quality.

Thermosets influence part durability, thermal resistance, and chemical stability, making them suitable for applications requiring long-term performance under stress. Their inability to be reprocessed affects material handling and waste management, requiring careful planning in mold setup and cycle timing. The selection of Thermosets in Injection Molding impacts tooling lifespan, production throughput, and post-processing requirements, making them integral to process design and product reliability.

Is phenolic in injection molding heat-resistant and strong?

Yes, phenolic used in injection molding is heat-resistant and strong. Phenolic belongs to the category of thermoset polymers identified as suitable for applications requiring dimensional stability and mechanical durability under elevated temperatures. The material undergoes an irreversible chemical reaction during molding, forming a rigid cross-linked structure that resists deformation and thermal breakdown. Phenolic contributes to production efficiency by reducing post-processing requirements and supporting high-strength applications across electrical, automotive, and industrial sectors.

What Are Elastomers in Injection Molding?

Elastomers in Injection Molding refer to polymer materials that exhibit elastic properties, allowing deformation under stress and recovery upon release. Elastomers are suitable for applications requiring flexibility, impact absorption, and surface grip across varied environmental conditions. Elastomers consist of long-chain molecules with cross-linked structures that support reversible stretching without permanent deformation. This behavior influences production efficiency by enabling rapid mold filling and consistent part ejection without cracking or warping. Machines configured for elastomer molding require precise temperature and pressure control to maintain flow characteristics and ensure proper vulcanization (curing) without premature curing. Machine parts (screws, barrels, and nozzles) must accommodate low-viscosity materials and support uniform distribution across the mold cavity.

Implementation types involving elastomers include overmolding, multi-shot molding, and insert molding, where soft zones are bonded to rigid substrates. Mold designs for elastomers incorporate venting systems, flexible gating strategies, and optimized cooling channels to manage shrinkage and maintain dimensional accuracy. The elasticity of the material affects mold surface finish, part geometry, and cycle timing, which contribute to tooling selection and maintenance planning.

Elastomers influence part performance by providing vibration damping, sealing capability, and ergonomic surface texture. Their role in injection molding extends across industries such as automotive, medical, consumer electronics, and industrial equipment, where durability and comfort remain essential. Material selection of Elastomers in Injection Molding affects mold longevity, production throughput, and post-processing requirements, making elastomers integral to functional design and manufacturing strategy.

Is TPE in injection molding flexible like rubber but processable like plastic?

Yes, TPE in injection molding is flexible like rubber but processable like plastic. Thermoplastic Elastomer (TPE) belongs to a class of materials known for its ability to combine elasticity with thermoplastic processing. The molecular structure of TPE supports reversible deformation under stress, which allows molded parts to stretch and recover without permanent damage. The combination of rubber-like performance and plastic-like processing makes it suitable for high-volume production requiring comfort, durability, and design flexibility.

What Are Specialty Materials in Injection Molding?

Specialty Materials in Injection Molding refer to engineered polymers and blends designed to meet advanced performance, regulatory, or environmental requirements. The specialty materials are non-standard options selected for their enhanced mechanical, thermal, chemical, or aesthetic properties. The materials influence production efficiency by supporting targeted functionality and reducing the need for secondary treatments. Specialty compounds allow manufacturers to meet industry-specific standards (flame retardancy, biocompatibility, or UV resistance). Their behavior under heat and pressure affects machine calibration, requiring precise control over temperature zones, screw speed, and injection pressure. Machine parts (barrels, nozzles, and mold inserts) must accommodate the flow characteristics and curing profiles of specialty resins.

Implementation types (overmolding, multi-shot molding, and insert molding) benefit from specialty materials due to their bonding compatibility and structural integrity. Mold design adapts to specialty compounds by incorporating venting systems, cooling channels, and surface treatments that support dimensional stability and surface finish. Specialty materials influence mold longevity, cycle time, and part geometry, which affects tooling selection and maintenance planning.

The use of specialty materials supports applications across automotive, aerospace, medical, and consumer electronics sectors. Their role in injection molding extends beyond basic functionality, contributing to product reliability, compliance, and lifecycle performance. The selection of Specialty Materials in Injection Molding affects every stage of production, from mold setup to post-processing, making specialty compounds essential to advanced manufacturing strategies.

Custom Formulated Materials represent a subset of specialty compounds designed to achieve specific performance goals not met by standard resins. These engineered blends are tailored through additives, fillers, or chemical treatments to enhance flame resistance, UV stability, or chemical durability. While custom formulations improve part reliability and allow compliance with demanding specifications in sectors like aerospace, automotive, and medical devices, they also require longer development times and higher upfront costs due to testing and validation needs.

Are custom compounds in injection molding tailored for flame-retardancy, UV resistance, or conductivity?

Yes, custom compounds in injection molding are tailored for flame-retardancy, UV resistance, or conductivity. Custom compounds are specialty materials engineered to meet advanced performance requirements in regulated and high-demand environments. They incorporate additives and reinforcements that modify thermal behavior, electrical properties, and environmental durability. Material selection affects tooling lifespan, cycle time, and post-processing requirements, making custom compounds essential to specialized manufacturing strategies.

What Are the Types of Injection Molding Molds?

The types of injection molding molds vary based on their structure, gating method, and compatibility with production scale, material behavior, and part geometry. Plate types include two-plate, three-plate, and stacked-plate molds. Two-plate molds are the most basic and widely used, ideal for simpler parts with straightforward designs. They consist of a cavity and core section that form the part. However, they can struggle with complex geometries, often requiring additional inserts or more advanced mold designs for intricate features. Three-plate molds introduce a third section that separates the molded parts from the runners, improving ejection efficiency and surface finish. These molds support more complex gating strategies, though they come with higher tooling costs and increased setup complexity. Stacked-plate molds offer multiple cavity levels within a single mold base, allowing for high-volume output without increasing the machine footprint. However, they introduce significant complexity and cost due to the precise alignment required across layers.

Runner types include cold runner and hot runner systems. Cold runner molds are unheated and direct molten plastic into the mold cavities, making them suitable for lower-volume production. However, they result in material waste as solidified runners must be removed after molding. On the other hand, hot runner molds keep the plastic molten in the runner system, reducing waste and improving material efficiency. The systems require a higher initial investment and are more complex to maintain due to the need for heating elements in the runner system.

Mold cavity designs can be single-cavity, multi-cavity, or family molds. Single-cavity molds produce one part per cycle and are typically used for low-volume production. They are simple but slower compared to multi-cavity molds, which can create multiple identical parts in one cycle. Multi-cavity molds are ideal for high-volume manufacturing, reducing the cost per part. However, they require precise flow balancing to ensure all cavities fill evenly, which involve adjusting runner sizes and gating locations. Family molds are designed to produce different parts in one cycle, which can optimize production when multiple components are needed. However, these molds come with the risk of uneven filling and dimensional inconsistencies due to differences in part size and geometry, requiring careful mold design and material flow management.

Each mold type supports specific manufacturing goals and influences tooling costs, cycle times, and part consistency. Understanding the characteristics of each mold type is crucial for selecting the right approach based on the part geometry, material properties, and production volume.

What Are the Types of Injection Molding?

- The types of Injection Molding are listed below

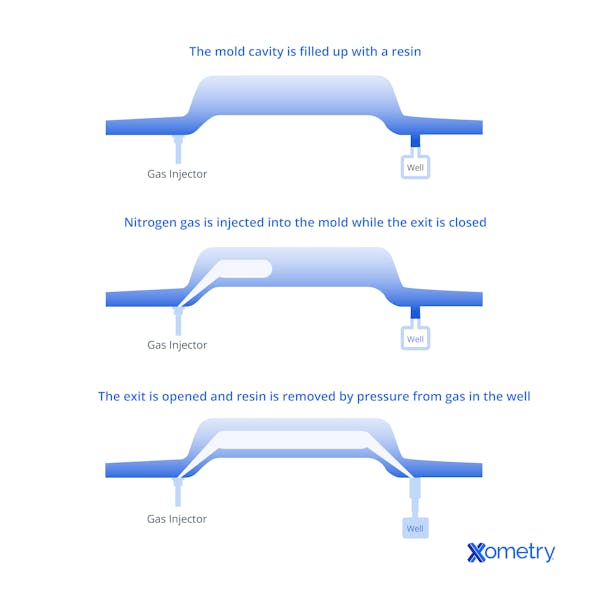

Gas-Assisted Injection Molding: The method injects nitrogen gas into the molten plastic to form hollow sections. It reduces material usage and improves surface finish in parts such as handles and panels.

- Thin-Wall Molding: Thin-wall molding produces lightweight parts with reduced cycle times. It suits packaging, containers, and electronic housings requiring minimal wall thickness.

- Liquid Silicone Injection Molding: The process uses two-part silicone compounds injected into heated molds. It supports flexible, heat-resistant products such as seals, gaskets, and baby care items.

- Structural Foam Molding: Structural foam molding introduces a foaming agent into the plastic to create a cellular core. It produces rigid, lightweight parts for furniture and equipment housings.

- Metal Injection Molding: Metal injection molding combines powdered metal with binders, followed by molding and sintering. It creates small, high-strength components for aerospace, firearms, and medical tools.

- Overmolding: Overmolding bonds two materials in a single part, such as a soft grip over a rigid handle. It improves ergonomics and adds functional layers to tools and electronics.

- Insert Molding: Insert molding embeds metal or other components into the plastic during molding. It supports threaded parts, electrical connectors, and reinforced assemblies.

- Co-Injection Molding (Sandwich Molding): The method injects two materials sequentially to form layered parts. It suits packaging and automotive panels requiring barrier layers or recycled cores.

- Multi-Shot / Multi-Material Molding: Multi-shot molding uses multiple injections to form complex parts with distinct zones. It supports toothbrushes, buttons, and multi-color components.

- Reaction Injection Molding (RIM): RIM mixes reactive chemicals that cure inside the mold. It produces lightweight, impact-resistant parts for automotive bumpers and enclosures.

- Micro Injection Molding: Micro molding creates miniature parts with tight tolerances. It supports medical devices, sensors, and microelectronics.

- Cold Runner Injection Molding: Cold runner systems use unheated channels to deliver plastic to the mold. They suit low-cost, simple molds but generate more waste.

- Hot Runner Injection Molding: Hot runner systems maintain molten plastic in heated channels. They reduce waste and support faster cycles in multi-cavity molds.

- Injection Compression Molding: The hybrid method combines compression and injection to form large or thick parts. It suits automotive components and structural panels.

- Cube, Rotary Molding: Cube molding rotates the mold during cycles to support multi-shot processes. It increases productivity for multi-material and multi-color parts.

1. Gas-Assisted Injection Molding

Gas-Assisted Injection Molding is a technique where pressurized inert gas (typically nitrogen) is injected into the mold after molten plastic, pushing the material towards the mold walls and leaving hollow sections. The method helps reduce material usage, creates lightweight parts, and promotes more uniform cooling, particularly in thicker sections of a part. The gas reduces warping, shrinkage, and sink marks during cooling by distributing pressure more evenly and allowing for faster cooling times.

The process offers advantages such as material reduction and faster cycle times, especially in large parts or those with complex geometries. However, there are some limitations, and gas flow control is simpler in single-cavity tools, but multi-cavity gas-assist is feasible with proper channel design and control. Complex multi-cavity molds with unique geometries experience difficulties with gas distribution. Certain materials, especially clear plastics, experience surface issues due to the interaction between the gas and material, though such issues are manageable with proper adjustments. Common materials used in gas-assisted injection molding include Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS), Polycarbonate (PC), High-Impact Polystyrene (HIPS), Nylon (PA), Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT), Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET), and Polypropylene (PP).

2. Thin-Wall Molding

Thin-Wall Molding enables the production of parts with wall thicknesses as thin as 0.5 mm to 2 mm, optimizing material use and reducing overall costs. The molding process is suited for small, high-precision parts such as electronic enclosures, medical device components, and tubing. The process requires higher injection pressures due to the reduced volume of material, ensuring that the plastic fills the mold quickly and evenly. Specialized thin-wall injection molding machines are designed for high precision and tight tolerances, typically within the range of ±0.1 mm, making them suitable for applications demanding tight-fit components.

The advantages of thin-wall molding include significant cost savings due to reduced material consumption, faster cycle times, and a decrease in the weight of molded parts, which can reduce transportation emissions. Thin-wall parts are ideal for fuel-based applications like automotive parts, where weight reduction is essential. The parts are typically made from recyclable plastics, further supporting sustainability goals.

However, the disadvantages include higher upfront costs for mold production and specialized molding machines. The machines need to handle high pressures and precise, low-tolerance molding. It requires highly trained technicians to monitor the process, identify potential defects, and ensure quality control. Mold life is affected by the high pressures required for thin-wall parts, demanding stress-resistant components in the machine. Common materials for thin-wall injection molding include nylon, polypropylene (PP), polyester, polystyrene, cellulose plastics, and polyoxymethylene (POM). These materials offer good fluidity, strength, and resistance to meet the demands of thin-wall molding applications.

3. Liquid Silicone Injection Molding

Liquid Silicone Injection Molding (LSR) is a unique injection molding process that uses liquid silicone rubber, a thermoset material, to produce high-quality, durable components. LSR involves injecting liquid silicone (at room temperature) into a heated mold, where it undergoes cross-linking (vulcanization) due to heat exposure, unlike traditional injection molding processes. The process imparts the flexibility, durability, and heat resistance that silicone is known for. LSR molding requires specialized equipment such as mixers, metering units, and sealing systems to ensure the correct mixing ratios and prevent contamination during injection.

LSR offers significant advantages over traditional thermoplastics, including biocompatibility, resistance to chemicals, and temperature extremes, and electrical conductivity, making it ideal for applications in medical devices, food-grade items, and electronic components. It produces smooth, high-precision parts with fewer defects, such as burrs and waste, especially when correctly engineered.

However, LSR does have its limitations. The vulcanization process is irreversible, meaning the molded parts cannot be reprocessed or recycled, unlike thermoplastic materials. LSR requires specialized molding equipment, which can be expensive and difficult to maintain. Common materials used in Liquid Silicone Injection Molding include standard silicone, medical-grade silicone, resistant silicones, and optical silicone, each suited for various high-performance applications.

4. Structural Foam Molding

Structural Foam Molding is an injection molding process that creates large, lightweight parts by introducing a blowing agent (nitrogen or a chemical blowing agent) into a molten polymer. The blowing agent causes the polymer to expand, forming a low-density foam core while the outer surface solidifies into a high-density skin. The skin provides strength, while the foam core reduces the overall weight of the part. Structural foam molding is ideal for producing large parts (automotive roofs, medical equipment housings, and consumer goods) due to its ability to produce parts with enhanced strength-to-weight ratios.

The key advantages of structural foam molding include the ability to produce large, cost-effective, lightweight, and strong parts. The process is particularly beneficial for creating parts with variable wall thickness and is resistant to warping, reducing stress during production. Structural foam parts are durable and exhibit high stiffness-to-weight ratios, making them easy to paint and handle during post-processing. They also show good dimensional stability under temperature variations.

However, there are some disadvantages, such as rougher surface finishes and the need for post-processing to improve the aesthetics. The molding process typically uses thicker wall sections than solid injection molding, but minimum thickness depends on the material and design. While it is effective for large parts, production speeds are generally slower than with other types of injection molding. Common materials used in structural foam molding include polyurethane, polycarbonate, ABS, and polybutylene terephthalate, among others, depending on the desired properties for the final part.

5. Metal Injection Molding

Metal Injection Molding (MIM) is a process used to manufacture high-precision, small metal parts by injecting a mixture of metal powder and binder into a mold, forming the part. The part undergoes debinding (a two-step process involving both thermal and solvent debinding) to remove the binder after molding, followed by sintering in a high-temperature furnace to fuse the metal particles, creating a dense and durable metal part.

MIM offers the advantage of producing complex and intricate metal components with high precision and minimal material waste. It is ideal for mass production of small parts (typically weighing less than 100g) that require fine details such as holes, knurling, and tight tolerances. The process is widely used in industries such as automotive, aerospace, medical devices, and electronics, where small, durable, and high-performance parts are essential.

The disadvantages of the metal injection molding include high initial equipment costs and limitations on part size (typically less than 100g), making it less suitable for larger components. The materials commonly used in MIM include stainless steel, titanium, tungsten carbide, cobalt-chrome alloys, and various nickel-based super alloys.

6. Overmolding

Overmolding is a type of injection molding where one material is molded over another to create a unified part. The method is ideal for applications that require different material properties in a single component. Initially, a base layer is molded, followed by the injection of a second material, which bonds to the first. The technique enables the integration of functional zones, such as rigid cores and flexible surfaces, without the need for additional assembly steps.

The benefits of overmolding include enhanced part durability, shorter assembly times, and the ability to combine materials with distinct characteristics. It ensures consistent layer alignment, improving product reliability and manufacturing efficiency. Overmolding enables the creation of ergonomic surfaces, vibration-dampening zones, and sealed interfaces within a single molding cycle.

However, overmolding presents challenges, including increased tooling complexity, longer cycle times, and higher production costs. Achieving proper material bonding and ensuring compatible material properties are crucial for the process. The selection of materials requires careful consideration to ensure good adhesion between layers, which limits material options and necessitates additional testing. Common materials used in overmolding include ABS, PC, PP, PE, TPU, TPE, nylon, and custom elastomers.

7. Insert Molding

Insert Molding is a specialized injection molding process where preformed components (inserts) are placed into the mold cavity and surrounded by molten plastic during the injection cycle. The method is ideal for producing parts that require integrated features such as fasteners, reinforcements, or electrical contacts. Insert molding creates a single bonded structure, combining the mechanical properties of the insert with the surrounding plastic material. It is commonly used in applications where precise alignment, mechanical strength, and material compatibility are essential for performance.

The key advantages of insert molding include reduced assembly time, improved part durability, and consistent alignment between the insert and the plastic. It lowers labor costs and reduces post-processing steps by eliminating the need for adhesives or mechanical fasteners. The process is highly effective for creating parts with tight tolerances and ensuring repeatable placement, making it suitable for high-volume production runs. The integration of multiple materials in a single part allows for multifunctional designs without increasing the component count.

However, insert molding has some disadvantages, including increased tooling complexity, longer cycle times, and limited material combinations. Achieving precise insert placement and ensuring a strong bond between the insert and plastic requires careful control over material compatibility and bonding conditions. The materials used must be thermally and mechanically compatible, and specialized equipment is needed to place the inserts correctly. Production delays can occur if the insert shifts during molding or fails to bond properly, resulting in part rejection or the need for rework.

Common materials used in insert molding include ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene), PC (Polycarbonate), PP (Polypropylene), PE (Polyethylene), nylon, PEEK (Polyether Ether Ketone), TPU (Thermoplastic Polyurethane), TPE (Thermoplastic Elastomer), and various custom elastomers.

8. Co-Injection Molding (Sandwich Molding)

Co-injection Molding (Sandwich Molding) involves injecting two different plastic materials into a single mold cavity to form a layered structure. One material forms the core, while the other surrounds it as the outer shell. The process supports the production of parts that require distinct internal and external properties. The outer layer is selected for surface finish or environmental resistance, while the core material contributes to structural integrity or cost efficiency. The method allows manufacturers to combine performance characteristics without assembling separate components.

The advantages of co-injection molding include reduced use of high-cost materials, improved surface quality, and the ability to incorporate recycled content into the core. The process supports dual functionality within a single mold cycle, which contributes to production efficiency and consistent part geometry. The layered structure allows for targeted material application, which supports design flexibility and resource management.

The disadvantages of a sandwich molding are increased tooling complexity, limited material compatibility, and higher setup requirements. The process demands precise control over injection timing and pressure to ensure proper bonding between layers. Material selection must account for thermal and mechanical compatibility, which restricts available combinations. Production risks increase if the interface between core and shell materials fails to bond correctly, leading to defects or rework. The common materials used in Co-Injection Molding (Sandwich Molding) include ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene), PC (Polycarbonate), PP (Polypropylene), PE (Polyethylene), PS (Polystyrene), nylon, recycled resins, and custom-filled compounds.

9. Multi-Shot / Multi-Material Molding

Multi-Shot / Multi-Material Molding is a type of injection molding where two or more plastic materials are sequentially injected into a single mold cavity to create a unified part. The method is particularly suited for applications that require distinct zones with different material properties, such as combining rigid and flexible areas within a single part. Each material is bonded either chemically or mechanically to the previous layer, creating a component that integrates multiple functionalities without the need for additional assembly.

The advantages of multi-shot molding include reduced assembly time, enhanced part consistency, and the ability to combine materials with varied properties, such as flexibility, impact resistance, or aesthetic finishes. The process ensures precise layer alignment and uniform bonding, which boosts product reliability and design versatility. Manufacturers create multifunctional components while maintaining dimensional accuracy and surface quality throughout the production cycle.

However, multi-shot molding comes with challenges, including increased tooling complexity, longer cycle times, and limited material compatibility. Each additional material or shot requires careful control over injection timing, pressure, and temperature, all of which can impact part quality and manufacturing efficiency. Material selection must ensure thermal and mechanical compatibility to avoid issues like delamination or weak bonding. It necessitates additional testing and qualification. Production delays can occur if the interface between layers fails to bond correctly, leading to defects and rework.

Common materials used in multi-shot molding include ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene), PC (Polycarbonate), PP (Polypropylene), PE (Polyethylene), TPU (Thermoplastic Polyurethane), TPE (Thermoplastic Elastomer), nylon, and custom elastomers. These materials are chosen for their compatibility in multi-shot processes, enabling the creation of parts with complex properties and superior performance characteristics.

10. Reaction Injection Molding (RIM)

Reaction Injection Molding (RIM) is a process in which two liquid components are mixed and injected into a mold, where they chemically react and cure into a solid part. The method is ideal for producing lightweight, durable, and complex components with low internal stress. The low-pressure injection helps maintain dimensional stability and reduces part distortion. RIM supports the creation of large, thin-walled parts and complex geometries that are difficult to achieve with other molding techniques.

The advantages of RIM include reduced tooling pressure, lower material density, and the ability to produce large parts with fine details. The process is effective for integrating functional additives such as reinforcements, fillers, and flame retardants, allowing manufacturers to tailor material properties. RIM is known for its low-pressure mold filling, dimensional stability, and ability to produce high-quality parts with intricate designs, although cycle times are typically longer than in thermoplastic injection molding. It is a cost-effective solution for low to medium volume production of parts that need structural integrity, flexibility, and durability.

However, RIM has limitations. It offers limited material selection, primarily thermoset polymers, which restricts its use for certain applications. The process requires precise mixing ratios, as any imbalance can lead to poor curing or part defects. Longer curing times compared to thermoplastic molding can slow production cycles, and material waste is a concern if the chemical reaction does not occur properly. RIM is less suited for high-volume production due to slower throughput and the need for specialized equipment.

The materials commonly used in RIM include Polyurethane, Polyurea, Epoxy, and Hybrid Thermoset Blends. These materials offer excellent mechanical properties, including impact resistance and flexibility, making them suitable for a wide range of applications, from automotive bumpers to medical enclosures.

11. Micro Injection Molding

Micro Injection Molding is a highly specialized manufacturing process used to produce tiny plastic components with tight tolerances and intricate details. The process involves specialized equipment capable of handling low shot volumes and fine mold features, making it ideal for industries that require miniature parts with high repeatability and consistent geometry. Micro injection molding is commonly applied in industries (electronics, medical devices, and automotive systems) where compact components must maintain dimensional accuracy and structural integrity. The method enables the production of highly intricate designs, often at a micrometer scale, without compromising material performance or surface quality.

The advantages of micro injection molding include reduced material waste, high efficiency in producing small parts, and the ability to maintain tight tolerances at high production volumes. The process is ideal for miniaturizing products, enabling the creation of complex shapes and intricate details that are difficult to achieve with traditional molding methods. Micro injection molding allows the integration of functional features within confined spaces, making it a preferred choice for high-precision applications.

However, disadvantages include higher tooling costs and increased complexity in mold design, as well as limited material flow control due to the small cavity sizes. It requires precise process control to avoid defects such as uneven filling and warping. The need for specialized molds and equipment raises initial investment costs, and material selection becomes critical to accommodate the small cavity sizes and ensure consistent material flow. Temperature variations and mold design issues lead to defects, such as incomplete filling or poor surface quality.

Common materials used in micro injection molding include PEEK (Polyether Ether Ketone), LCP (Liquid Crystal Polymer), Polycarbonate (PC), Polypropylene (PP), Polyethylene (PE), Nylon, ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene), and custom medical-grade resins. These materials are selected based on their thermal stability, mechanical strength, and processability for high-precision applications.

12. Cold Runner Injection Molding

Cold Runner Injection Molding uses a mold system where plastic flows through unheated channels before reaching the cavity. The method is a cost-effective option for producing parts with standard shapes and moderate production volumes. It involves injecting molten plastic into a mold with a runner system kept at ambient temperature. The runner material is ejected along with the part once the plastic fills and solidifies in the cavity. Cold runner systems support a variety of thermoplastics and enable simple mold design. Their applications do not require complex gating or high-speed manufacturing.

Cold runner injection molding offers several advantages (lower tooling costs, easier maintenance, and compatibility with a wide variety of materials). The runner system reduces initial expenses and simplifies mold manufacturing because it does not include heating elements. Cold runner molds are ideal for multi-cavity setups and accommodate frequent material changes without needing extensive cleaning. The process allows for greater design flexibility and maintains consistent production quality for moderate volumes.

Cold runner injection has disadvantages (higher material waste, longer cycle times, and lower energy efficiency). The runner material must be trimmed and discarded or recycled after each cycle, increasing post-processing efforts. Cold runner systems offer limited control over flow dynamics, which can compromise surface finish and dimensional accuracy in complex parts. The requirement to eject the runner with each part extends cycle times and reduces productivity in high-volume production. Common materials for cold runner injection molding include ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene), PC (Polycarbonate), PP (Polypropylene), PE (Polyethylene), PS (Polystyrene), nylon, PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride), acrylic, and Acetal.

13. Hot Runner Injection Molding

Hot Runner Injection Molding uses a heated manifold system to deliver molten plastic directly into the mold cavity without solidifying the runners. The method is ideal for high-volume production of complex parts, as it ensures continuous material flow, reduces waste, and eliminates the need to remove and recycle cold runners after each cycle. Hot runner systems enable precise control over injection timing and pressure, improving material use efficiency and part quality consistency, especially for multi-cavity molds.

Advantages of such a method include reduced material waste, faster cycle times, and better surface finishes due to uniform material flow and the absence of solidified runners. It improves dimensional accuracy and reduces defects like sink marks, which are typically caused by uneven cooling.

However, disadvantages include higher tooling costs due to the need for specialized heated components, increased maintenance complexity from potential nozzle blockages, and longer setup times because of the precise temperature control required. Temperature control and material compatibility are critical factors in achieving consistent results, as improper heating or unsuitable materials can lead to part inconsistencies.

Common materials used in Hot Runner Injection Molding include ABS, Polycarbonate (PC), Polypropylene (PP), Polyethylene (PE), Polystyrene (PS), nylon, acetal, acrylic, and thermoplastic elastomers, which offer suitable flow characteristics and thermal stability for the process.

14. Injection Compression Molding

Injection Compression Molding is a manufacturing process that combines injection and compression by injecting molten material into a partially open mold, then closing the mold to compress the material and complete cavity filling. This method is ideal for producing durable components with consistent geometry and reduced internal stress. It supports applications that require high strength, dimensional stability, and uniform surface finish. Inserts or reinforcements can be integrated during the molding process.

The advantages of injection compression molding include reduced material waste, lower tooling costs, and improved mechanical properties. The process is energy-efficient as it does not require high-pressure equipment, simplifying maintenance. Uniform pressure distribution across the mold ensures consistent part thickness and reduces the risk of warping.

However, compression molding has some limitations, including longer cycle times, limited design flexibility, and increased sensitivity to material placement. The process requires precise control over temperature and pressure to avoid defects like voids or incomplete curing. It is less suitable for parts with intricate geometries or undercuts, due to the directional nature of the molding process.

Common materials used in injection compression molding include Polyurethane, Epoxy, Phenolic, Silicone, Polyester, Vinyl Ester, Thermoset composites, Sheet Molding Compounds (SMC), and Bulk Molding Compounds (BMC).

15. Cube, Rotary Molding

Cube or Rotary Molding is an advanced multi-station injection molding process that utilizes a rotating mold mechanism to streamline operations like injection, cooling, and ejection within a single cycle. The method is particularly advantageous for high-volume production, where efficiency and multi-material integration are crucial. The process involves a rotating cube or carousel mold that moves between stations, each dedicated to a specific task. One section injects material, another cools, and a third ejects the finished part. The continuous rotation allows for synchronized operations, significantly reducing downtime and increasing throughput, especially in processes requiring multi-shot molding or the combination of different materials or colors in a single part.

The primary advantages of cube or rotary molding include faster cycle times, enhanced production efficiency, and the capability to integrate multiple materials or components within a single mold cycle. The rotating structure facilitates parallel processing, which maximizes operational efficiency and minimizes idle time. The process promotes consistent part quality across large volumes and offers flexibility in design configurations, allowing manufacturers to combine functional zones or embed features into a single part.

However, cube or rotary molding also has disadvantages. These include higher tooling costs, increased mechanical complexity, and limited suitability for low-volume production. The rotating mold system requires precise alignment and regular maintenance to prevent failures. Setup times increase due to the need for synchronized control over multiple stations and careful material coordination. Mold design and temperature management also present challenges, as improper calibration lead to inconsistencies in part quality. Common materials used in cube or rotary molding include ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene), PC (Polycarbonate), PP (Polypropylene), PE (Polyethylene), TPU (Thermoplastic Polyurethane), TPE (Thermoplastic Elastomer), nylon, and custom elastomers.

What Are the Advantages of Injection Molding?

The Advantages of Injection Molding are listed below.

- High Production Efficiency: Injection molding allows quick, repeatable production of thousands to millions of parts with minimal cycle time once the mold is set up, making it ideal for scalable manufacturing without losing consistency.

- Exceptional Part Consistency: The process ensures uniform units with tight tolerances and identical dimensions, crucial for components needing precise fit and function.

- Material Versatility: A variety of thermoplastics and elastomers allows manufacturers to choose materials for strength, flexibility, chemical resistance, or appearance. Thermosets are processed with specialized equipment but are less common in conventional injection molding. Additives (colorants or fillers) are added during molding.

- Complex Geometry Capability: Intricate designs, undercuts, and fine details are molded without extra machining. Multi-cavity and multi-material molds expand design options while reducing costs.

- Low Waste Generation: Excess material from runners and sprues is recycled and reused, reducing waste. The process is efficient, with most material becoming part of the final product.

- Improved Surface Finish: Molded parts have smooth surfaces, minimizing post-processing. Textures, logos, and patterns are embedded into the mold for aesthetic or functional reasons.

- Cost-Effective at Scale: The per-unit cost drops with volume while initial tooling costs are high, making injection molding viable for large runs where tooling costs are amortized.

- Automation Compatibility: Injection molding integrates with robotics and automation, streamlining ejection, inspection, and packaging, reducing labor costs and increasing throughput.

What Are the Disadvantages of Injection Molding?

The disadvantages of injection molding are listed below.

- Incompatible with Small Production Runs: Custom tooling (molds, fixtures, jigs, and other equipment) requires a significant investment to develop. Additional costs include mold setup and purchasing plastic for molding. The production volume of injection-molded parts must be economically viable.

- Extended Initial Lead Times: Manufacturing tooling typically takes 4 to 12 weeks, depending on complexity and supplier capacity, while producing and shipping parts adds 2 to 4 weeks. Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining or 3D printing offer quicker turnaround options for companies without existing injection molding setups.

- Limited Design Flexibility: Modifying it is either difficult or unattainable once a mold is made. Major design changes need a new mold, which necessitates a design completion before production.

- Limitations on the Size of Parts Produced: Very large parts are feasible but require high-tonnage presses and molds, which significantly increase cost and setup complexity. Examples include car door panels and large appliance housings.

- Designs Are Challenging to Achieve: Parts produced using this method must have uniform wall thickness, sufficient draft angles for ejection, and limited undercuts. Undercuts can be molded using slides or lifters but increase tooling cost and complexity.

When to Use Injection Molding?

The situations when to use Injection Molding are listed below.

- Mass Production of Identical Parts: Injection molding excels when thousands to millions of uniform components are needed, reducing per-unit cost after tooling.

- Complex Part Designs with Tight Tolerances: Injection Molding supports intricate geometries, undercuts, and fine details that are difficult to achieve with other manufacturing methods.

- High-Speed Manufacturing Requirements: Cycle times are short once molds are built, typically ranging from seconds to under a minute per part depending on size and material, making it ideal for rapid output in consumer, automotive, and medical sectors.

- Material-Specific Performance Needs: A wide range of thermoplastics and additives are used to meet strength, flexibility, or chemical resistance requirements.

- Consistent Surface Finish and Appearance: Molds are engineered to produce parts with specific textures, gloss levels, or patterns without secondary finishing.

- Integrated Features to Reduce Assembly: Multi-cavity and multi-material molds allow for complex assemblies to be produced as single units, streamlining production.

- Projects with Long-Term Production Plans: The upfront tooling investment pays off when parts are needed over extended periods, ensuring repeatability and cost efficiency.

- Applications Requiring Lightweight Components: Plastic parts molded with precision provide strength-to-weight benefits in aerospace, electronics, and consumer goods.

What Are the Injection Molding Application Examples?

The Injection Molding Application Examples are listed below.

- Automotive Components: Parts (dashboards, bumpers, and trim panels) are molded for durability, dimensional accuracy, and resistance to heat and impact.

- Food and Beverage Packaging: Containers, caps, and dispensers are produced with food-safe plastics that meet hygiene standards and support high-volume distribution.

- Packaging and Handling Components (Reels, Spools, Bobbins): Standardized molded parts such as plastic reels, wire spools, bobbins, and cable guides are produced for use in packaging, material handling, and automated assembly systems.

- Toys and Figurines: Colorful and detailed plastic toys are manufactured with consistent shapes and textures, supporting mass production and safety compliance.

- Furniture Components: Chair bases, armrests, and decorative trims are molded for strength and aesthetic consistency in residential and commercial furniture.

- Fixtures and Fasteners: Clips, brackets, and mounting hardware are produced with tight tolerances to ensure reliable assembly and structural support.

- Mechanical Components (Gears, Valves, Pumps, Linkages): Functional parts requiring precise geometry and wear resistance are molded for use in industrial machinery and consumer products.

- Electronic Hardware and Housings: Enclosures for devices (routers, controllers, and sensors) are molded to protect internal components and support ergonomic design.

- Medical Device Components: Syringes, diagnostic housings, and surgical tool casings are molded with biocompatible materials that meet regulatory standards.

- General Plastic Parts: Everyday items (handles, knobs, trays, and utility covers) are molded for consistent quality and cost-effective production.

Summary

Xometry provides a wide range of manufacturing capabilities including CNC machining, 3D printing, injection molding, laser cutting, and sheet metal fabrication. Get your instant quote today.

Disclaimer

The content appearing on this webpage is for informational purposes only. Xometry makes no representation or warranty of any kind, be it expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or validity of the information. Any performance parameters, geometric tolerances, specific design features, quality and types of materials, or processes should not be inferred to represent what will be delivered by third-party suppliers or manufacturers through Xometry’s network. Buyers seeking quotes for parts are responsible for defining the specific requirements for those parts. Please refer to our terms and conditions for more information.