Creep Deformation refers to the time-dependent, permanent strain experienced by a material under constant stress and temperature over an extended period. The creep deformation occurs when a material is subjected to long-term loading, causing it to gradually deform if the stress level remains below the material's yield strength. Creep is significant in materials science, engineering, and 3D printing because it influences the long-term performance and reliability of stressed components.

Understanding creep in materials is crucial for predicting the behavior of materials in high-temperature environments or applications involving common long-term loads. For example, metal components in turbines, engines, and structural elements experience creep, leading to premature failure if not properly accounted for in the design process. The creep curve is used to characterize the material's response over time, displaying the relationship between strain and time under constant stress and temperature.

The process of creep consists of three stages (primary, secondary, and tertiary). The primary stage shows an initial rapid rate of deformation, which gradually slows down in the secondary stage, where the deformation rate becomes steady. The tertiary stage marks the final phase, where the material experiences an accelerated strain rate, eventually leading to fracture. There are mechanisms that contribute to creep (dislocation movement, grain boundary sliding, and diffusion processes), which are temperature-dependent. Understanding the stages and mechanisms is important for designing materials that maintain structural integrity over time under constant stress.

What is Creep Deformation?

Creep deformation refers to the slow, time-dependent change in a material's shape when it is subjected to a constant stress at high temperatures. Creep occurs when a material is subjected to constant stress—often below its yield strength—at elevated temperatures for an extended period, resulting in permanent deformation. The process is typical in high-temperature environments, where materials under sustained stress deform slowly without immediate failure. Creep deformation causes slow, continuous shape change at high temperatures through mechanisms (atomic diffusion, dislocation movement, and grain boundary sliding). The processes gradually alter a material's properties, impacting performance and lifespan. Understanding creep is vital for maintaining the structural integrity of components under long-term stress, influencing material choices for such applications.

What Is Creep (Deformation) in Materials Science?

Creep (deformation) in materials science is the slow, time-dependent strain that occurs when a material is subjected to constant stress at high temperatures. Creep results in permanent deformation, unlike elastic deformation, which is reversible. The phenomenon is most important in materials that experience sustained loading—often below their yield strength—at elevated temperatures, where atomic movement is more pronounced.

Understanding creep in materials science is vital because it affects the structural integrity of components. Mechanical properties (strength, ductility, or toughness) degrade as materials undergo creep, risking failure in long-term stress applications. Creep occurs in metals, polymers, and ceramics through mechanisms (dislocation movement, grain boundary sliding, and diffusion), causing ongoing shape changes. Different materials creep at various rates depending on composition, temperature, and stress. Accurate prediction of creep is necessary for ensuring the durability and performance of materials in high-stress, high-temperature environments.

What Is Creep (Deformation) in Concrete?

Creep (deformation) in concrete refers to the gradual, time-dependent strain that occurs when concrete is subjected to a sustained load over an extended period. The phenomenon happens even when the applied stress is lower than the concrete’s ultimate compressive strength. Creep in concrete is significant because it leads to the slow and continuous deformation of structures, potentially affecting their long-term performance and stability.

Creep in concrete depends on hydration, moisture, temperature, and aggregate type. Its internal microstructure, with hydrated cement and pores, allows water movement under load, causing deformation. Creep is most significant early but persists over the structure's lifetime, risking deflection, misalignment, and stress on joints. Engineers use creep curves to predict deformation and plan for durability and safety.

What Is Creep (Deformation) in Steel?

Creep (deformation) in steel refers to the gradual, time-dependent elongation or deformation of steel when subjected to a constant load or stress at high temperatures. Creep results in permanent deformation over time, unlike elastic deformation, which is reversible. Creep becomes significant in steel at temperatures above ~0.4 × melting temperature (in Kelvin), which is ~400°C to 500 °C for most steels.

Creep in steel involves dislocation movement, grain boundary sliding, and atomic diffusion, which cause slow deformation at higher temperatures where atomic mobility increases. The creep rate depends on temperature, stress, material composition, and load duration, affecting steel's long-term performance in high-temperature industries (turbines, pressure vessels, and structural beams). Understanding and predicting creep is vital for safety and durability in demanding environments.

What is Creep (Deformation) in Polymers?

Creep (deformation) in polymers refers to the gradual, time-dependent deformation that occurs when a polymer material is subjected to a constant load or stress. The deformation process takes place over an extended period and results in permanent changes in the shape of the material. Polymers exhibit more pronounced creep behavior due to their molecular structure, unlike metals, which are more rigid and less susceptible to molecular rearrangement under stress. The polymers' long-chain molecules allow them to flow or stretch when exposed to constant force, especially at elevated temperatures. Creep in polymers depends on factors (polymer type, stress, and temperature). Higher temperatures speed up creep in polymers due to increased molecular motion, while lower temperatures slow it down. Polymers with lower glass transition temperatures are more susceptible because their chains are more flexible. Creep impact products (seals, gaskets, and structural parts in automotive, aerospace, and construction), making understanding it vital for selecting long-lasting materials.

What is Thermal Creep?

Thermal creep is the time-dependent deformation of materials at high temperatures under constant load, driven by the combined effects of temperature and sustained stress. Atomic vibrations increase with heat, causing progressive, irreversible deformation that can lead to failure. It involves dislocation movement, weakened by thermal energy, with the rate rising at higher temperatures. Crystalline structures facilitate dislocation, making them vulnerable, while polymers, metals, and ceramics undergo thermal creep, more so in polymers at lower temperatures. Understanding it is necessary for selecting materials for high-temperature, stressed environments.

What is Plastic Creep?

Plastic creep is the permanent deformation of a material under constant load over time, especially when it exceeds its elastic limit. Elastic deformation is reversible, but all forms of creep involve permanent deformation. There's no standard phenomenon known as 'elastic creep. Plastic creep occurs through dislocation movement and grain boundary sliding, leading to permanent elongation or compression. Polymers, with long-chain molecules, exhibit more molecular mobility, causing deformation as chains stretch and rearrange. The rate and extent of creep depend on temperature, stress, and material properties. Polymers are more sensitive to lower temperatures and less resistant to long-term deformation than metals.

How Does Creep (Deformation) Work?

Creep deformation works by a material undergoes gradual, time-dependent strain while subjected to a constant stress at elevated temperatures. Creep results in permanent changes to the material's shape, unlike elastic deformation, which is reversible. Internal mechanisms, when a material is subjected to a sustained load (dislocation movement in metals or molecular chain slippage in polymers), lead to continuous deformation.

The rate of creep is influenced by several factors (applied stress, temperature, and material composition). Atomic vibrations increase at higher temperatures, allowing dislocations or molecular chains to move more freely, which accelerates the creep process. The material undergoes three stages during creep. Primary is where the strain rate decreases, secondary is where the strain rate becomes constant, and tertiary is where the material experiences an accelerated strain rate until failure. Understanding creep behavior is necessary for predicting the long-term performance of materials in environments where they are exposed to sustained stresses (high-temperature or high-stress applications).

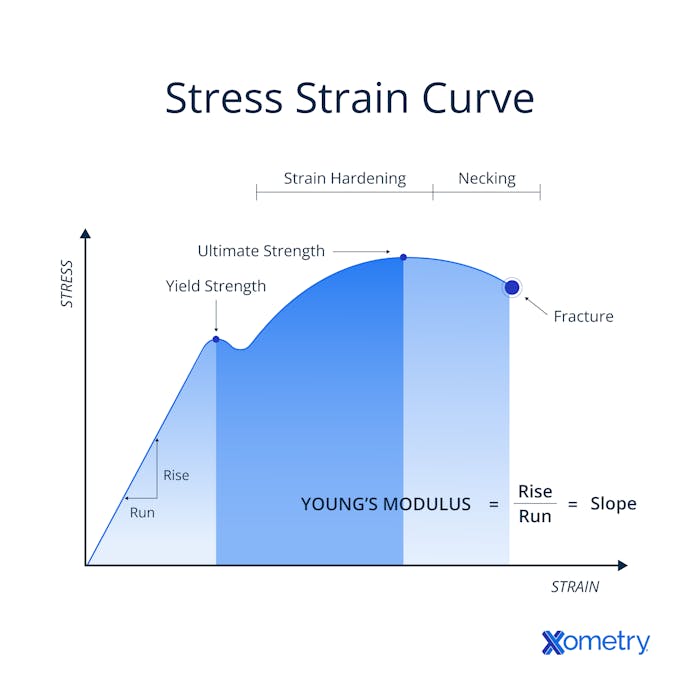

How does Creep Affect Material Strength?

Creep affects material strength by gradually reducing tensile strength and fatigue life, compromising the long-term reliability of materials. Creep causes permanent deformation, reducing the material’s ability to withstand stress over time. In metals, creep causes dislocation movement, grain boundary sliding, and void formation, increasing failure risk under sustained loads. Polymers are prone to creep, which stretches and rearranges chains, weakening the material’s strength.

Creep decreases a material's fatigue life by causing cumulative damage under cyclic loading. Continuous deformation leads to cracks, fractures, or microstructural changes, weakening the material. Creep triggers phase separation or microstructural shifts in alloys, reducing strength and fatigue resistance. Long-term high temperatures and stresses hasten creep, impairing reliability in critical applications. It is for high-temperature materials (turbines or pressure vessels), where sustained stress and heat diminish performance.

How does Creep Occur in Mechanical Components?

Creep in mechanical components occurs when a material undergoes gradual deformation under a constant stress, typically at elevated temperatures. Creep occurs at elevated temperatures even when stress is below the yield strength. The deformation is driven by the movement of dislocations in the material’s microstructure, which becomes more pronounced as the temperature increases.

Stress, load, and temperature influence creep in components. Sustained loads cause microscopic material changes, leading to deformation, at high temperatures that speed up atomic vibrations and dislocation movement. Creep causes beam deflection and dimensional changes in gears and shafts, risking structural integrity and function. Knowing how creep develops is crucial for designing durable materials and structures in high-temperature or heavy-load environments.

How Does Creep (Deformation) Work in 3D Printing?

Creep deformation in 3D printing depends on many factors, such as the technology used to print the part, the material used, and the post-processing techniques followed. The normal viscoelastic behavior of polymers applies when 3D printing in plastic using FFF (Fused Filament Fabrication). The method means that if the part is exposed to constant stress, the molecular chains within the material will slip past each other, resulting in creep. It is a problem as 3D printing plastics generally have lower melting temperatures and are therefore more readily affected by environmental temperatures, which can accelerate creep.

What Is the Importance of the Creep (Deformation) Test?

A creep test is important because it allows engineers to design parts while understanding the relationship between stress, temperature, and creep rate to ensure that a part does not fail at loads below its yield strength at elevated temperatures. A creep deformation test is performed by subjecting a sample to a constant tensile load and temperature to plot the strain developed as a function of time for metals.

Compressive creep tests are used to develop the behavior of the material under prolonged loads and increased temperatures for brittle materials. Creep tests provide insight by defining the secondary creep rate, which is used to design components for multi-decade service life, and the time to rupture, which is used to design relatively short-term components (turbine blades).

How To Read a Creep (Deformation) Graph?

To read a creep (deformation) graph, there are three stages that help visualize and are broken down, which delve into. The idea of how the graph looks and the information it tells is shown in the image below.

The first section shows a material when it first starts undergoing long-lasting strain and stress. The second portion of the graph is when creep deformation really starts happening at a constant rate. The third area shows the creep strain rate of the material as it works its way to the point of rupturing. Hotter temperatures normally lead to higher strain rates and speed up the timeline of material finally rupturing.

What does a Creep Diagram Show?

A creep diagram shows the relationship between strain and time when the material is under constant stress and temperature. The horizontal axis shows time, while the vertical axis indicates strain. The curve features three main stages of creep (primary, secondary, and tertiary). Primary creep starts with a decreasing strain rate as the material adapts to the applied stress. Secondary creep is characterized by a nearly steady strain rate, forming the longest and most stable phase. Tertiary creep involves an increasing strain rate, leading to eventual material failure. The diagrams are useful in materials testing for assessing long-term deformation, estimating service life, and informing design choices for structures subject to continuous loads and high temperatures.

How to Read a Creep Curve Diagram?

To read a creep curve diagram, there are three steps to follow. First, identify the primary creep. Observe the initial portion of the curve where strain increases rapidly, but the rate gradually decreases. The stage reflects material adjustment to applied stress and microstructural resistance to deformation. Second, interpret secondary creep. Focus on the middle section of the curve where strain progresses at a nearly constant rate. The stage represents the most stable phase of deformation and defines the long-term service behavior of the material.

Lastly, recognize tertiary creep. Examine the final portion of the curve where strain accelerates sharply until failure occurs. The stage indicates microstructural breakdown and marks the end of material strength under sustained stress.

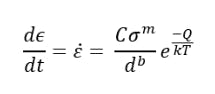

What Is the General Creep Equation?

The general creep equation describes the time-dependent deformation of materials subjected to constant stress at elevated temperatures, providing a mathematical framework for predicting strain as a function of stress, time, and temperature.

The general creep equation is expressed in the form of,

Creep equation.

C - Constant, and changes depending on the creep mechanism and the material

σ - The stress that is being applied to the material

m, b - Exponents that depend on the creep mechanism

d - The average grain size of the material

Q - Activation energy of the deformation

k - Boltzmann’s constant

T - Absolute temperature

The relationship accounts for the influence of stress level, exposure time, and thermal conditions on creep deformation. The equation reflects the fact that creep strain increases with higher stress and longer exposure, while elevated temperature accelerates the rate of deformation due to thermally activated processes. The constants within the equation vary depending on microstructural characteristics (grain size, dislocation density, and the presence of precipitates). The general creep equation is applied in materials science to estimate the service life and performance of metals, polymers, and ceramics under high-temperature operating conditions.

How to Calculate Creep Rate?

To calculate creep rate, follow the five steps below.

- Define the formula. Use the standard creep rate equation expressed as strain change over time: The formula represents the slope of the creep curve during a given stage of deformation.

- Measure the strain change. Record the difference in strain values between two points on the curve. Ensure the strain is expressed in dimensionless form, such as millimeters per millimeter (mm/mm).

- Determine the time interval. Identify the time difference corresponding to the measured strain change. Express the time in hours or seconds, depending on the testing conditions.

- Calculate the creep rate. Divide the strain change by the time interval to obtain the creep rate.

- Interpret the result. Compare the calculated creep rate with material performance requirements. A higher creep rate indicates reduced long-term strength and reliability under sustained stress.

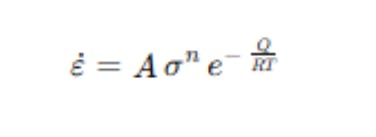

What are the Formulas for Creep Strain?

The formulas for creep strain are listed below.

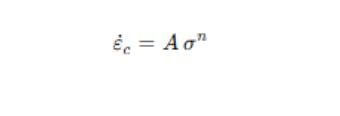

- Define Norton’s Law. Express the creep strain rate as

Capture the combined effects of stress, temperature, and material constants on deformation.

- Simplify the Power Law. Write creep strain rate as ε˙=K⋅σn when the temperature is constant. Represent stress sensitivity through an exponent “𝑛” derived from experimental testing. Below is another simple equation.

“Creep deformation represents a quiet but decisive mode of material failure, emerging not from sudden overload but from the slow accumulation of irreversible strain under sustained stress and temperature. Its danger lies in subtlety: components may appear intact while internal damage steadily evolves. Effective engineering design therefore treats time itself as a load, requiring materials and geometries that can tolerate years of gradual microstructural change. Mastery of creep behavior transforms uncertainty about long-term performance into quantifiable, manageable risk.”

What Are the 3 Stages of Creep (Deformation)?

Three stages of Creep (Deformation) are listed below.

1. Primary Creep

The creep rate decreases due to strain hardening, but the “elastic phase” happens immediately before creep begins. The elastic phase and the creep rate reduce as the material undergoes strain hardening.

2. Secondary Creep

Secondary creep is the next stage, which goes by steady-state creep. The stage that tends to be the longest phase of creep. During secondary creep, the rate of strain is balanced, with hardening and softening effects in equilibrium, not dominated by softening. The secondary creep rate is special, while the whole graph is important. Engineers use a parameter when they’re designing structures and objects.

3. Tertiary Creep

Tertiary creep is the last stage on the graph. The stage of creep that gives a good visual of the point when stress and temperature finally lead to rupturing and creep failure due to internal voids, micro-cracks, and grain boundary separation.

What Are the Different Mechanisms of Creep (Deformation)?

Different mechanisms of Creep (Deformation) are listed below.

1. Nabarro-Herring Creep

Low stress and high temperatures are needed for Nabarro-Herring Creep to take place. The atoms that are in the crystal lattice of the material’s grains diffuse, and vacancies in the structure appear as the temperature gets hotter. Materials with larger grains see a slower Nabarro-Herring creep rate, and smaller grains see a quicker rate.

2. Creep of Polymers

Creep happens to polymers that are put under stress and hot temperatures. Polymer creep can occur at room temperature, especially for amorphous polymers near or above their glass transition temperature (Tg). The main mechanism found in the creep of polymers is the polymer’s chains sliding. Crystalline polymers are found, and it’s a more common deformation in amorphous types.

3. Dislocation Creep

Dislocation Creep occurs through the motion of dislocations, primarily by glide and climb under high stress. Often modeled using Norton’s power law. Sometimes called power law creep, the dislocation creep or deformation depends on atoms moving horizontally or vertically in a parallel or perpendicular manner, causing vacancies.

4. Coble Creep

Coble creep happens at cooler temperatures. The creep happens on the boundary of the material’s grain (rather than inside of it), which is why searing does not need hot temperatures for it to take place. The boundary grains shift perpendicular to the stress, causing the coble creep.

5. Solute-Drag Creep

Solute-Drag creep happens to alloyed materials, which have elements that are normally highly creep-resistant. Creep resistance increases when solute atoms form atmospheres around dislocations that impede their motion, known as solute-drag creep.

6. Harper-Dorn Creep

Another form of dislocation creep, but the size of the grain doesn’t impact the strain rate. There are a few factors that need to line up for Harper-Dorn creep to happen. Firstly, grains have to be larger (at a minimum of 0.5 mm), the composition must be elementally pure (no less than 99.95%), and there must be a little dislocation density present. It doesn’t take much for it to show up. The creep occurs with temperatures that are 35% to 60% of the melting temp of the material and low-stress levels.

7. Grain Boundary Sliding

The grain boundary sliding or superplastic creep (common in fine-grained materials). The mechanism of creep is where prolonged strain leads to slow, permanent deformation of materials. The grain boundary sliding is the movement of material along the boundaries between individual grains within a polycrystalline structure.

What is the Mechanism of Creep in Metals?

The mechanism of creep in metals occurs at the atomic and microstructural levels, involving several processes that lead to time-dependent deformation under constant stress. The movement of dislocations is a defect in the crystal structure of metals that moves when stress is applied, causing the material to deform. The dislocations accumulate, leading to permanent changes in the material's shape.

Grain boundary diffusion contributes to creep by enabling atoms near boundaries to become more mobile at high temperatures, weakening the material and accelerating deformation. Metals (superalloys) are vulnerable in high-temperature environments (turbines). They deform over time due to dislocation movement and grain boundary diffusion, despite their advanced microstructures to resist creep. Understanding the mechanisms is vital for designing durable, high-temperature materials.

What Types of Materials Are Subjected To Creep (Deformation)?

The types of materials that are subjected to creep (deformation) include metals, polymers, ceramics, and concrete. Creep occurs in materials under constant stress at high temperatures, driven by atomic diffusion and changes in microstructure. Metals creep at approximately half the melting temperature (in Kelvin). Polymers (polyethylene, polypropylene, and polylactic acid) creep at room temperature because of their viscoelastic properties, where molecular chains move over time. Ceramics (silicon nitride and alumina) creep at elevated temperatures, primarily due to grain boundary diffusion and microstructural stability. Concrete and rocks creep, with long-term deformation affected by moisture, porosity, and sustained loads. Each material type has unique creep mechanisms, but all exhibit the gradual buildup of strain under constant stress.

Which Materials are Prone to Creep?

Materials prone to creep include metals at elevated temperatures, polymers under sustained stress, composites with weak matrix phases, and high-temperature alloys subjected to extreme service conditions. Creep susceptibility depends on atomic bonding, microstructural stability, and operating environment.

Creep is time-dependent plastic deformation under constant stress at high temperatures. Metals typically creep at temperatures above ~0.5 × melting temperature (in Kelvin). Polymers creep significantly at ambient conditions due to viscoelastic chains. Composites creep when their polymer matrix or interfaces deform under prolonged load. Superalloys resist creep better, but deform under extreme conditions.

Metals creep via dislocation glide, climb, and diffusion. Polymers deform by chain slippage and relaxation. Composites creep when the matrix dominates, weakening the structure. High-temperature alloys resist creep through solid-solution strengthening and precipitation hardening, but long exposure causes microstructural degradation.

Comparative susceptibility of creep and other materials is shown in the table below.

| Material Class | Susceptibility to Creep | Primary Mechanisms | Factors Influencing Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

Material Class Metals | Susceptibility to Creep High at homologous temperatures | Primary Mechanisms Dislocation glide, dislocation climb, diffusion | Factors Influencing Behavior Grain size, alloying elements, stress level |

Material Class Polymers | Susceptibility to Creep Significant even at ambient temperature | Primary Mechanisms Chain slippage, molecular relaxation | Factors Influencing Behavior Temperature, molecular weight, crystallinity |

Material Class Composites | Susceptibility to Creep Moderate to high, depending on the matrix | Primary Mechanisms Matrix creep, interfacial debonding | Factors Influencing Behavior Fiber type, matrix composition, load transfer |

Material Class High-temperature alloys | Susceptibility to Creep Lower but present under extreme service | Primary Mechanisms Solid-solution strengthening, precipitation hardening | Factors Influencing Behavior Alloy design, microstructural stability, operating temperature |

What is Creep in Civil Engineering?

Creep in civil engineering is defined as the gradual, time-dependent deformation of materials subjected to sustained stress. Concrete exhibits creep due to microstructural changes and moisture redistribution in the cement paste, leading to gradual strain without increased load. Soils experience creep when particles shift under continuous stress, as seen in fine-grained soils (clays), which deform due to water movement and structural alterations. Structural elements (steel members and prestressed tendons) undergo creep when under prolonged stress; metals deform through dislocation movement and diffusion at high temperatures, while tendons lose tension via concrete creep and steel relaxation.

Long-term deformation affects structures by increasing deflections, redistributing stresses, and reducing serviceability. Bridges experience girder sagging and pier stress from creep, while buildings face settlement and cracking. Creep causes excessive deflection, misalignment, and durability issues, impacting infrastructure performance.

At What Temperature Does Creep Become Important?

The temperature at which creep becomes important depends entirely on the material. For example, some polymers experience creep at room temperature, whereas metals experience creep from about 40% of their melting temperature.

What Is Creep Failure?

Creep failure is a time-dependent plastic deformation of a material that has been exposed to constant stress, with higher temperatures increasing the likelihood of creep failure. Creep failure occurs at the tertiary-creep stage. It normally follows an extended stage of steady-state creep. The failure occurs relatively quickly when compared to the steady state phase and occurs with the formation of internal voids, grain boundary separation, and microcracks.

What are the Effects of Creep on Material Strength?

The effects of creep on material strength are listed below.

- Reduction in Load-Bearing Capacity: Creep reduces the ability of a material to sustain applied loads over extended service periods. Progressive deformation under constant stress decreases stiffness and leads to diminished structural reliability.

- Fracture Risks: Creep accelerates microstructural damage that increases susceptibility to crack initiation and propagation. Prolonged exposure to stress and temperature conditions raises the likelihood of a catastrophic fracture.

- Design Considerations to Prevent Failure: Creep requires engineers to account for time-dependent deformation in material selection and structural design. Proper safety margins, stress limits, and thermal management strategies are necessary to maintain long-term performance.

How To Prevent Creep (Deformation)?

There are a few preventative measures you can put in place to keep creep at bay and factors to keep an eye on when you’re working with materials that are subject to the kind of deformation. The first step is getting to grips with the stages of creep in various materials. It is helpful to note when the materials in use reach their secondary phase, so the selected option handles the required conditions.

Use superalloys, directionally solidified or single-crystal metals, or dispersion-strengthened alloys to resist creep, not cause it. Taking some time to catch it before it’s too late, since the creep needs time to really set in. Going for materials with high melting points or keeping the temperature surrounding it as cool as possible (if and when possible) prevents it.

What Are the Factors That Can Prevent Creep (Deformation)?

Creep deformation is easily eliminated by following the three suggested methods below:

1. Stages of Creep

Creep occurs in three stages (primary, secondary, and tertiary). The secondary stage of creep is what is used to determine if a material is compatible with a specific strain and temperature combination. The secondary stage takes the longest time and is defined by having a constant strain rate. The material must remain in this second phase during normal operating conditions to prevent creep.

2. Materials Selection

Creep deformation is reduced or eliminated by selecting the correct material for the application. Materials with large grains are more resistant to certain types of creep, specifically diffusion creep. Materials without any grains are highly creep-resistant. A metal without grains is produced by directionally casting a part to ensure it is made up of a single homogenous crystal. Some iron alloys are made to be creep-resistant with a specific precipitate. Carbide, for example, tends to collect at the grain boundaries to stabilize them, thereby preventing dislocation from occurring at these points. Dispersion strengthening does not prevent dislocations from forming, but obstructs their motion, which increases creep resistance.

3. Various Working Conditions

Creep requires time and temperature. The easiest way to prevent creep deformation is to ensure that the operating temperature is as low as possible. Design the part with a lower service life to ensure it is replaced while creep deformation levels are still low, if it is not possible. Materials with higher melting points are selected.

How to Minimize Creep in Materials?

To minimize creep in materials, follow the four steps listed below.

- Improve alloys. Strengthen materials by introducing alloying elements such as chromium, molybdenum, or nickel that stabilize grain boundaries and resist dislocation movement. Alloy development increases creep resistance in metals used for turbines, boilers, and high-temperature structural components.

- Adjust load. Reduce applied stress levels to limit the driving force for creep deformation under constant service conditions. Lowering mechanical loads extends service life in applications (pressure vessels and pipelines).

- Optimize temperature. Maintain operating conditions below the critical temperature range where creep mechanisms accelerate due to atomic diffusion. Controlled thermal environments reduce strain accumulation in metals, polymers, and ceramics exposed to long-term stress.

- Use coatings or heat treatments. Apply protective coatings or perform heat treatments to stabilize microstructures and reduce creep susceptibility. While refining grain size strengthens materials in many cases (e.g., yield strength via Hall-Petch), larger grains improve creep resistance by reducing grain boundary diffusion and sliding.

Frequently Asked Questions About Creep Deformation

Can Creep (Deformation) Be Fixed?

Creep deformation is permanent and does not reverse as the material is deformed plastically. The only way to fix creep deformation is to change the part or use a material that does not creep under normal operating conditions.

What Is the Difference Between Creep and Brittle Failure?

Creep is a relatively slow form of failure that is dependent on prolonged stress at elevated temperatures. Creep occurs well below the yield point of a material. Brittle failure often occurs below the ultimate tensile strength, especially in the presence of stress concentrators or flaws.

How to Recognize Creep in Materials

Recognizing creep in materials begins by observing the dimensional changes. Detect gradual elongation, contraction, or distortion in a component subjected to constant stress. Dimensional variation over time indicates the accumulation of creep strain. Second, record the rate of deformation under sustained load and elevated temperature. A decreasing rate followed by a steady rate and eventual acceleration reflects primary, secondary, and tertiary creep stages. Third, examine surfaces for microcracks, voids, or localized roughness caused by prolonged stress exposure. The irregularities signal microstructural damage associated with creep progression. Fourth, track the reductions in tensile strength, hardness, or stiffness during long-term service. Altered mechanical performance demonstrates the weakening effect of creep on material integrity. Fifth, analyze grain boundary sliding, void formation, or phase transformations through microscopy. Microstructural evolution provides direct evidence of creep mechanisms at work. Lastly, record accelerated strain leading to fracture under constant stress conditions. Rapid deformation in the tertiary stage confirms the final phase of creep failure.

What is a Common Result of Creep?

A common result of creep is permanent deformation, which happens when a material gradually and irreversibly changes shape under constant stress over time. This results in sagging, causing components to lose their original form, misalign, or become structurally unstable. Cracks develop within the material as creep strain accumulates, weakening its integrity and possibly leading to failure.

Sustained loading causes the microstructure to deteriorate, speeding up deformation. The degradation raises the risk of mechanical failure in high-stress settings or at elevated temperatures. A material's resistance to creep is vital for its long-term reliability, and failure due to creep causes damage or the breakdown of mechanical systems if deformation surpasses acceptable limits.

Disclaimer

The content appearing on this webpage is for informational purposes only. Xometry makes no representation or warranty of any kind, be it expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or validity of the information. Any performance parameters, geometric tolerances, specific design features, quality and types of materials, or processes should not be inferred to represent what will be delivered by third-party suppliers or manufacturers through Xometry’s network. Buyers seeking quotes for parts are responsible for defining the specific requirements for those parts. Please refer to our terms and conditions for more information.